Tvillingfotoner fra forskellige kvanteprikker

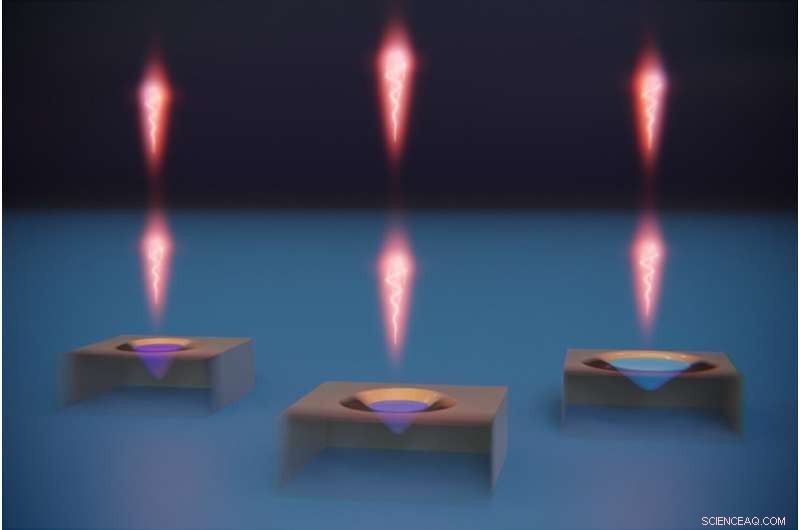

Selvom Basel-forskernes kvanteprikker er forskellige, udsender de nøjagtigt identiske lyspartikler. Kredit:University of Basel, Institut for Fysik

Identiske lyspartikler (fotoner) er vigtige for mange teknologier, der er baseret på kvantefysik. Et team af forskere fra Basel og Bochum har nu produceret identiske fotoner med forskellige kvanteprikker - et vigtigt skridt hen imod applikationer som tryksikker kommunikation og kvanteinternettet.

Mange teknologier, der gør brug af kvanteeffekter, er baseret på nøjagtigt lige store fotoner. Det er imidlertid ekstremt vanskeligt at producere sådanne fotoner. Ikke alene skal de have præcis samme bølgelængde (farve), men deres form og polarisering skal også matche.

Et team af forskere ledet af Richard Warburton ved University of Basel, i samarbejde med kolleger ved University of Bochum, er nu lykkedes med at skabe identiske fotoner, der stammer fra forskellige og vidt adskilte kilder.

Enkelte fotoner fra kvanteprikker

I deres eksperimenter brugte fysikerne såkaldte kvanteprikker, strukturer i halvledere på kun få nanometer store. I kvanteprikkerne er elektroner fanget, så de kun kan antage meget specifikke energiniveauer. Lys udsendes ved overgang fra et niveau til et andet. Ved hjælp af en laserpuls, der udløser en sådan overgang, kan enkelte fotoner således skabes ved et tryk på en knap.

"In recent years, other researchers have already created identical photons with different quantum dots," explains Lian Zhai, a postdoctoral researcher and first author of the study that was recently published in Nature Nanotechnology . "To do so, however, from a huge number of photons they had to pick and choose those that were most similar using optical filters." In that way, only very few usable photons remained.

Warburton and his collaborators chose a different, more ambitious approach. First, the specialists in Bochum produced extremely pure gallium arsenide from which the quantum dots were made. The natural variations between different quantum dots could thus be kept to a minimum. The physicists in Basel then used electrodes to expose two quantum dots to precisely tuned electric fields. Those fields modified the energy levels of the quantum dots, and they were adjusted in such a way that the photons emitted by the quantum dots had precisely the same wavelength.

93% identical

To demonstrate that the photons were actually indistinguishable, the researchers sent them onto a half-silvered mirror. They observed that, almost every time, the light particles either passed through the mirror as a pair or else were reflected as a pair. From that observation they could conclude that the photons were 93% identical. In other words, the photons formed twins even though they were "born" completely independently of one another.

Moreover, the researchers were able to realize an important building block of quantum computers, a so-called controlled NOT gate (or CNOT gate). Such gates can be used to implement quantum algorithms that can solve certain problems much faster than classical computers.

"Right now our yield of identical photons is still around one percent," Ph.D. student Gian Nguyen concedes. Together with his colleague Clemens Spindler he was involved in running the experiment. "We already have a rather good idea, however, how to increase that yield in the future." That would make the twin-photon method ready for potential applications in different quantum technologies. + Explore further

Researchers develop ideal single-photon source

Varme artikler

Varme artikler

-

Nanopartikler, der klæber sår sammenSvinetarme blev brugt til at teste den nye nanopartikel-baserede vævslim. Kredit:Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology På trods af medicinske fremskridt, sårrelaterede ko

Nanopartikler, der klæber sår sammenSvinetarme blev brugt til at teste den nye nanopartikel-baserede vævslim. Kredit:Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology På trods af medicinske fremskridt, sårrelaterede ko -

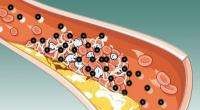

Nye nanopartikler gør blodpropper synligeEt blodkar (øverst) med revnet aterosklerotisk plak, vist med gult, udvikler en blodprop. Nanopartiklerne, vist i blåt og sort, er målrettet mod et protein i blodproppen kaldet fibrin, vist i lyseblå.

Nye nanopartikler gør blodpropper synligeEt blodkar (øverst) med revnet aterosklerotisk plak, vist med gult, udvikler en blodprop. Nanopartiklerne, vist i blåt og sort, er målrettet mod et protein i blodproppen kaldet fibrin, vist i lyseblå. -

Forskere overvinder tekniske forhindringer i søgen efter billige, holdbar elektronik og solcellerLys udsendes fra ophidsede argongasatomer, der strømmer gennem glasrøret i en plasma -reaktor. Plasmaet er et reaktivt miljø, der bruges til at producere silicium -nanokrystaller, der kan anvendes på

Forskere overvinder tekniske forhindringer i søgen efter billige, holdbar elektronik og solcellerLys udsendes fra ophidsede argongasatomer, der strømmer gennem glasrøret i en plasma -reaktor. Plasmaet er et reaktivt miljø, der bruges til at producere silicium -nanokrystaller, der kan anvendes på -

Første opdagelse af en naturlig topologisk isolatorMineralet Kawazulite er en naturlig “topologisk isolator, ”Et materiale, der kunne have applikationer i en ny genre af supercomputere. Kredit:American Chemical Society (Phys.org) - I et skridt mod

Første opdagelse af en naturlig topologisk isolatorMineralet Kawazulite er en naturlig “topologisk isolator, ”Et materiale, der kunne have applikationer i en ny genre af supercomputere. Kredit:American Chemical Society (Phys.org) - I et skridt mod

- Scholes finder en ny magnetfelteffekt i diamagnetiske molekyler

- Abell 1033:At gå modigt ind i kolliderende galaksehobe

- Hvordan laver man en transportbånd til en skole Project

- Typer af slanger i Delaware

- Iltmigrering ved heterostrukturgrænsefladen

- Kemiker syntetiserer guldbaserede elektrokatalysatorer