Nanoterapi giver nyt håb for behandling af type 1-diabetes

Kredit:Unsplash/CC0 Public Domain

Personer, der lever med type 1-diabetes, skal omhyggeligt følge de foreskrevne insulinkure hver dag og modtage injektioner af hormonet via sprøjte, insulinpumpe eller andet udstyr. Og uden holdbare langtidsbehandlinger er dette behandlingsforløb en livslang dom.

Bugspytkirtlens øer styrer insulinproduktionen, når blodsukkerniveauet ændres, og ved type 1-diabetes angriber og ødelægger kroppens immunsystem sådanne insulinproducerende celler. Ø-transplantation er dukket op i løbet af de sidste par årtier som en potentiel kur mod type 1-diabetes. Med sunde transplanterede øer behøver type 1-diabetespatienter muligvis ikke længere insulininjektioner, men transplantationsindsatsen har mødt tilbageslag, da immunsystemet fortsætter med at afvise nye øer. Nuværende immunsuppressive lægemidler tilbyder utilstrækkelig beskyttelse af transplanterede celler og væv og er plaget af uønskede bivirkninger.

Nu har et team af forskere ved Northwestern University opdaget en teknik, der hjælper med at gøre immunmodulering mere effektiv. Metoden bruger nanobærere til at rekonstruere det almindeligt anvendte immunsuppressive rapamycin. Ved hjælp af disse rapamycin-ladede nanobærere genererede forskerne en ny form for immunsuppression, der var i stand til at målrette mod specifikke celler relateret til transplantationen uden at undertrykke bredere immunresponser.

Artiklen blev offentliggjort i dag i tidsskriftet Nature Nanotechnology . Northwestern-teamet ledes af Evan Scott, Kay Davis-professoren og en lektor i biomedicinsk teknik ved Northwesterns McCormick School of Engineering og mikrobiologi-immunologi ved Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, og Guillermo Ameer, Daniel Hale Williams-professor i biomedicinsk teknik. hos McCormick og kirurgi ved Feinberg. Ameer fungerer også som direktør for Center for Advanced Regenerative Engineering (CARE).

Specificering af kroppens angreb

Ameer har arbejdet på at forbedre resultaterne af øtransplantation ved at give øer et konstrueret miljø ved at bruge biomaterialer til at optimere deres overlevelse og funktion. Imidlertid forbliver problemer forbundet med traditionel systemisk immunsuppression en barriere for den kliniske behandling af patienter og skal også behandles for virkelig at have en indvirkning på deres pleje, sagde Ameer.

"Dette var en mulighed for at samarbejde med Evan Scott, en leder inden for immunoengineering, og engagere sig i et konvergensforskningssamarbejde, der var godt udført med enorm opmærksomhed på detaljer af Jacqueline Burke, en National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellow," sagde Ameer.

Rapamycin er velundersøgt og almindeligvis brugt til at undertrykke immunrespons under andre typer behandling og transplantationer, bemærkelsesværdigt for dets brede vifte af virkninger på mange celletyper i hele kroppen. Typisk indgivet oralt, skal rapamycins dosis overvåges nøje for at forhindre toksiske virkninger. Alligevel har det ved lavere doser ringe effektivitet i tilfælde som ø-transplantation.

Scott, også medlem af CARE, sagde, at han ønskede at se, hvordan stoffet kunne forbedres ved at putte det i en nanopartikel og "kontrollere, hvor det går hen i kroppen."

"For at undgå de brede virkninger af rapamycin under behandling, gives lægemidlet typisk i lave doser og via specifikke administrationsveje, hovedsageligt oralt," sagde Scott. "But in the case of a transplant, you have to give enough rapamycin to systemically suppress T cells, which can have significant side effects like hair loss, mouth sores and an overall weakened immune system."

Following a transplant, immune cells, called T cells, will reject newly introduced foreign cells and tissues. Immunosuppressants are used to inhibit this effect but can also impact the body's ability to fight other infections by shutting down T cells across the body. But the team formulated the nanocarrier and drug mixture to have a more specific effect. Instead of directly modulating T cells—the most common therapeutic target of rapamycin—the nanoparticle would be designed to target and modify antigen presenting cells (APCs) that allow for more targeted, controlled immunosuppression.

Using nanoparticles also enabled the team to deliver rapamycin through a subcutaneous injection, which they discovered uses a different metabolic pathway to avoid extensive drug loss that occurs in the liver following oral administration. This route of administration requires significantly less rapamycin to be effective—about half the standard dose.

"We wondered, can rapamycin be re-engineered to avoid non-specific suppression of T cells and instead stimulate a tolerogenic pathway by delivering the drug to different types of immune cells?" Scott said. "By changing the cell types that are targeted, we actually changed the way that immunosuppression was achieved."

A 'pipe dream' come true in diabetes research

The team tested the hypothesis on mice, introducing diabetes to the population before treating them with a combination of islet transplantation and rapamycin, delivered via the standard Rapamune oral regimen and their nanocarrier formulation. Beginning the day before transplantation, mice were given injections of the altered drug and continued injections every three days for two weeks.

The team observed minimal side effects in the mice and found the diabetes was eradicated for the length of their 100-day trial; but the treatment should last the transplant's lifespan. The team also demonstrated the population of mice treated with the nano-delivered drug had a "robust immune response" compared to mice given standard treatments of the drug.

The concept of enhancing and controlling side effects of drugs via nanodelivery is not a new one, Scott said. "But here we're not enhancing an effect, we are changing it—by repurposing the biochemical pathway of a drug, in this case mTOR inhibition by rapamycin, we are generating a totally different cellular response."

The team's discovery could have far-reaching implications. "This approach can be applied to other transplanted tissues and organs, opening up new research areas and options for patients," Ameer said. "We are now working on taking these very exciting results one step closer to clinical use."

Jacqueline Burke, the first author on the study and a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellow and researcher working with Scott and Ameer at CARE, said she could hardly believe her readings when she saw the mice's blood sugar plummet from highly diabetic levels to an even number. She kept double-checking to make sure it wasn't a fluke, but saw the number sustained over the course of months.

Research hits close to home

For Burke, a doctoral candidate studying biomedical engineering, the research hits closer to home. Burke is one such individual for whom daily shots are a well-known part of her life. She was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes when she was nine, and for a long time knew she wanted to somehow contribute to the field.

"At my past program, I worked on wound healing for diabetic foot ulcers, which are a complication of Type 1 diabetes," Burke said. "As someone who's 26, I never really want to get there, so I felt like a better strategy would be to focus on how we can treat diabetes now in a more succinct way that mimics the natural occurrences of the pancreas in a non-diabetic person."

The all-Northwestern research team has been working on experiments and publishing studies on islet transplantation for three years, and both Burke and Scott say the work they just published could have been broken into two or three papers. What they've published now, though, they consider a breakthrough and say it could have major implications on the future of diabetes research.

Scott has begun the process of patenting the method and collaborating with industrial partners to ultimately move it into the clinical trials stage. Commercializing his work would address the remaining issues that have arisen for new technologies like Vertex's stem-cell derived pancreatic islets for diabetes treatment.

The paper is titled "Subcutaneous nanotherapy repurposes the immunosuppressive mechanism of rapamycin to enhance allogeneic islet graft viability." + Udforsk yderligere

Cell research offers diabetes treatment hope

Varme artikler

Varme artikler

-

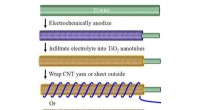

Forskere skræddersyr strømkilde til bærbar elektronikRadialt justerede titaniumoxidnanorør øger overfladearealet, at pakke mere kraft i tøjets rammer. Kredit:Udlånt af tidsskriftet Energy Storage Materials Bærbare strømkilder til bærbar elektronik e

Forskere skræddersyr strømkilde til bærbar elektronikRadialt justerede titaniumoxidnanorør øger overfladearealet, at pakke mere kraft i tøjets rammer. Kredit:Udlånt af tidsskriftet Energy Storage Materials Bærbare strømkilder til bærbar elektronik e -

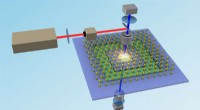

Mærkelig effekt øger muligheden for mindre, smartere optiske filtreEn gengivelse af den eksperimentelle opsætning brugt af Nebraskas Xia Hong og hendes kolleger. Lys reflekteres ned til nanostrukturen af molybdendisulfid (gul og blågrøn gitter) og PZT (blå og grøn)

Mærkelig effekt øger muligheden for mindre, smartere optiske filtreEn gengivelse af den eksperimentelle opsætning brugt af Nebraskas Xia Hong og hendes kolleger. Lys reflekteres ned til nanostrukturen af molybdendisulfid (gul og blågrøn gitter) og PZT (blå og grøn) -

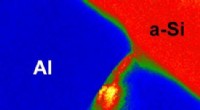

De fedeste halvleder nanotrådeTransmissionselektronmikrofotografi af et tværsnit af et aluminium-silicium-dobbeltlag under annealing. Billedet viser, at silicium strømmer ind i mellemrummene mellem de tilstødende aluminiumskrystal

De fedeste halvleder nanotrådeTransmissionselektronmikrofotografi af et tværsnit af et aluminium-silicium-dobbeltlag under annealing. Billedet viser, at silicium strømmer ind i mellemrummene mellem de tilstødende aluminiumskrystal -

Interaktiv størrelseskontrol af katalysatornanopartiklerForskere fra Institut for Fysisk Kemi ved det polske Videnskabsakademi i Warszawa har udviklet en interaktiv metode til at ændre størrelsen af katalysatornanopartiklerne under strømmen i mikrofluidi

Interaktiv størrelseskontrol af katalysatornanopartiklerForskere fra Institut for Fysisk Kemi ved det polske Videnskabsakademi i Warszawa har udviklet en interaktiv metode til at ændre størrelsen af katalysatornanopartiklerne under strømmen i mikrofluidi

- Rekonstruering af vulkanudbrud for at hjælpe videnskabsmænd med at forudsige klimarisici

- Ny klasse af nanopartikler giver billigere, lettere solceller udendørs

- Hvordan påvirker forurening udefra indendørs luftkvalitet

- Billede:Jorden og en formørket måne

- Bedre metoder forbedrer målinger af rekreativt vandkvalitet

- Plasmaacceleration:Det hele er med i blandingen