Superledende røntgenlaser når driftstemperaturen koldere end det ydre rum

Kredit:SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

Beliggende 30 fod under jorden i Menlo Park, Californien, er en halv kilometer lang tunnelstrækning nu koldere end det meste af universet. Den rummer en ny superledende partikelaccelerator, en del af et opgraderingsprojekt til Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) røntgenfri elektronlaser ved Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

Besætninger har med succes afkølet acceleratoren til minus 456 grader Fahrenheit - eller 2 Kelvin - en temperatur, hvor den bliver superledende og kan booste elektroner til høje energier med næsten ingen energi tabt i processen. Det er en af de sidste milepæle, før LCLS-II vil producere røntgenimpulser, der i gennemsnit er 10.000 gange lysere end LCLS, og som ankommer op til en million gange i sekundet - en verdensrekord for nutidens mest kraftfulde røntgen- strålelyskilder.

"På blot et par timer vil LCLS-II producere flere røntgenimpulser, end den nuværende laser har genereret i hele sin levetid," siger Mike Dunne, direktør for LCLS. "Data, der engang kunne have taget måneder at indsamle, kunne produceres på få minutter. Det vil tage røntgenvidenskaben til næste niveau, bane vejen for en helt ny række undersøgelser og fremme vores evne til at udvikle revolutionerende teknologier til at adressere nogle af de mest dybtgående udfordringer, som vores samfund står over for."

Med disse nye muligheder kan videnskabsmænd undersøge detaljerne i komplekse materialer med hidtil uset opløsning for at drive nye former for databehandling og kommunikation; afsløre sjældne og flygtige kemiske begivenheder for at lære os, hvordan man skaber mere bæredygtige industrier og rene energiteknologier; studere, hvordan biologiske molekyler udfører livets funktioner for at udvikle nye typer lægemidler; og kig ind i kvantemekanikkens bizarre verden ved direkte at måle individuelle atomers bevægelser.

En afslappende bedrift

LCLS, verdens første hårde røntgen-frielektronlaser (XFEL), producerede sit første lys i april 2009 og genererede røntgenimpulser en milliard gange lysere end noget, der var kommet før. It accelerates electrons through a copper pipe at room temperature, which limits its rate to 120 X-ray pulses per second.

In 2013, SLAC launched the LCLS-II upgrade project to boost that rate to a million pulses and make the X-ray laser thousands of times more powerful. For that to happen, crews removed part of the old copper accelerator and installed a series of 37 cryogenic accelerator modules, which house pearl-like strings of niobium metal cavities. These are surrounded by three nested layers of cooling equipment, and each successive layer lowers the temperature until it reaches nearly absolute zero—a condition at which the niobium cavities become superconducting.

"Unlike the copper accelerator powering LCLS, which operates at ambient temperature, the LCLS-II superconducting accelerator operates at 2 Kelvin, only about 4 degrees Fahrenheit above absolute zero, the lowest possible temperature," said Eric Fauve, director of the Cryogenic Division at SLAC. "To reach this temperature, the linac is equipped with two world-class helium cryoplants, making SLAC one of the significant cryogenic landmarks in the U.S. and on the globe. The SLAC Cryogenics team has worked on site throughout the pandemic to install and commission the cryogenic system and cool down the accelerator in record time."

One of these cryoplants, built specifically for LCLS-II, cools helium gas from room temperature all the way down to its liquid phase at just a few degrees above absolute zero, providing the coolant for the accelerator.

On April 15, the new accelerator reached its final temperature of 2 K for the first time and today, May 10, the accelerator is ready for initial operations.

"The cooldown was a critical process and had to be done very carefully to avoid damaging the cryomodules," said Andrew Burrill, director of SLAC's Accelerator Directorate. "We're excited that we've reached this milestone and can now focus on turning on the X-ray laser."

Bringing it to life

In addition to a new accelerator and a cryoplant, the project required other cutting-edge components, including a new electron source and two new strings of undulator magnets that can generate both "hard" and "soft" X-rays. Hard X-rays, which are more energetic, allow researchers to image materials and biological systems at the atomic level. Soft X-rays can capture how energy flows between atoms and molecules, tracking chemistry in action and offering insights into new energy technologies. To bring this project to life, SLAC teamed up with four other national labs—Argonne, Berkeley Lab, Fermilab and Jefferson Lab—and Cornell University.

Jefferson Lab, Fermilab and SLAC pooled their expertise for research and development on cryomodules. After constructing the cryomodules, Fermilab and Jefferson Lab tested each one extensively before the vessels were packed and shipped to SLAC by truck. The Jefferson Lab team also designed and helped procure the elements of the cryoplants.

"The LCLS-II project required years of effort from large teams of technicians, engineers and scientists from five different DOE laboratories across the U.S. and many colleagues from around the world," says Norbert Holtkamp, SLAC deputy director and the project director for LCLS-II. "We couldn't have made it to where we are now without these ongoing partnerships and the expertise and commitment of our collaborators."

Toward first X-rays

Now that the cavities have been cooled, the next step is to pump them with more than a megawatt of microwave power to accelerate the electron beam from the new source. Electrons passing through the cavities will draw energy from the microwaves so that by the time the electrons have passed through all 37 cryomodules, they'll be moving close to the speed of light. Then they'll be directed through the undulators, forcing the electron beam on a zigzag path. If everything is aligned just right—to within a fraction of the width of a human hair—the electrons will emit the world's most powerful bursts of X-rays.

This is the same process that LCLS uses to generate X-rays. However, since LCLS-II uses superconducting cavities instead of warm copper cavities based on 60-year-old technology, it can can deliver up to a million pulses per second, 10,000 times the number of X-ray pulses for the same power bill.

Once LCLS-II produces its first X-rays, which is expected to happen later this year, both X-ray lasers will work in parallel, allowing researchers to conduct experiments over a wider energy range, capture detailed snapshots of ultrafast processes, probe delicate samples and gather more data in less time, increasing the number of experiments that can be performed. It will greatly expand the scientific reach of the facility, allowing scientists from across the nation and around the world to pursue the most compelling research ideas. + Udforsk yderligere

Upgraded X-ray laser shows its soft side

Varme artikler

Varme artikler

-

Mod en nanomekanisk kvanteomstillingKredit:Andreas Hüttel Fysikere ved Universität Regensburg har koblet vibrationerne fra et makromolekyle - et kulstof nanorør - til et mikrobølgehulrum, skabe et nyt og meget miniaturiseret optomek

Mod en nanomekanisk kvanteomstillingKredit:Andreas Hüttel Fysikere ved Universität Regensburg har koblet vibrationerne fra et makromolekyle - et kulstof nanorør - til et mikrobølgehulrum, skabe et nyt og meget miniaturiseret optomek -

Hvornår er månens træk på jorden den stærkeste?Styrken af månetyngdekraften er relateret til månens masse - som ikke ændrer sig - og afstanden mellem månen og jorden. Når månen følger sin elliptiske bane rundt om Jorden, øges og aftager afsta

Hvornår er månens træk på jorden den stærkeste?Styrken af månetyngdekraften er relateret til månens masse - som ikke ændrer sig - og afstanden mellem månen og jorden. Når månen følger sin elliptiske bane rundt om Jorden, øges og aftager afsta -

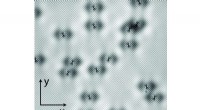

Elektronorbitaler kan have nøglen til at forene konceptet om høj temperatur superledningDette billede produceret af det spektroskopiske billeddannelsesscanningstunnelmikroskop afslører placeringen af hvert atom på overfladen, samt hver eneste atomfejl i synsfeltet. De hvide prikker, de

Elektronorbitaler kan have nøglen til at forene konceptet om høj temperatur superledningDette billede produceret af det spektroskopiske billeddannelsesscanningstunnelmikroskop afslører placeringen af hvert atom på overfladen, samt hver eneste atomfejl i synsfeltet. De hvide prikker, de -

Ikke-invasive optiske sensorer giver hjerneovervågning i realtid efter slagtilfældeForskerne udviklede et optisk overvågningssystem, der hurtigt og nemt kan bruges i Akutafdelingen. Brug af pandesensorer til at udsende og detektere laserlys, det nye system kunne afsløre tidlige tegn

Ikke-invasive optiske sensorer giver hjerneovervågning i realtid efter slagtilfældeForskerne udviklede et optisk overvågningssystem, der hurtigt og nemt kan bruges i Akutafdelingen. Brug af pandesensorer til at udsende og detektere laserlys, det nye system kunne afsløre tidlige tegn

- Den fantastiske verden af flammebolde, donuts og hestesko

- Indsigt i antarktisk landskab holder prognoserne for istab på radaren

- Volkswagen, Google samarbejder om kvantecomputerforskning

- Den spiser alt - den nye race af skovbrande, der er umulige at forudsige

- For at se en komet form, et rumfartøj kunne tage med på en rejse mod solen

- Eksempler på naturkatastrofer og de miljømæssige ændringer, der opstår