Forskere tilbyder virksomheder en ny kemi for grønnere polyurethan

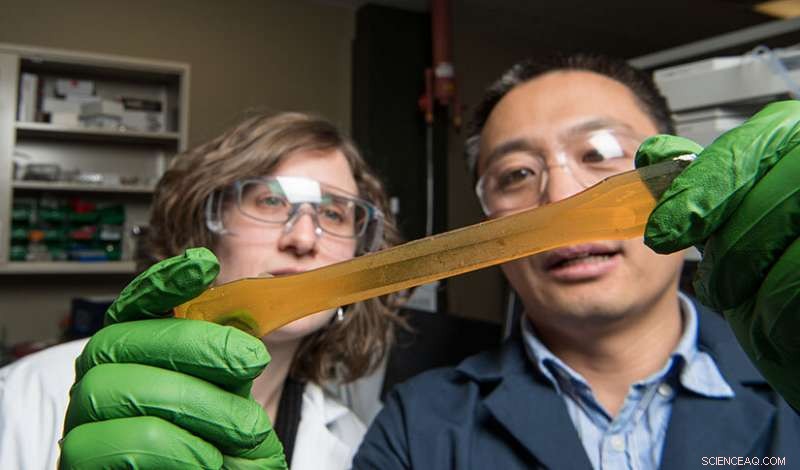

En banebrydende formel for vedvarende energi-NREL-forsker Tao Dong (højre) og tidligere praktikant Stephanie Federle (til venstre) undersøger biobaseret, ikke -toksisk polyurethanharpiks, et lovende alternativ til konventionel polyurethan. Kredit:Dennis Schroeder, NREL

Uden det, Verden er måske lidt mindre blød og lidt mindre varm. Vores fritidstøj kaster måske mindre vand. Indlægssålene i vores sneakers giver muligvis ikke den samme terapeutiske svangestøtte. Trækornet i færdige møbler "dukker måske ikke op".

Ja, polyurethan - en almindelig plast i applikationer lige fra sprøjtbare skum til klæbemidler til syntetiske tøjfibre - er blevet en fast bestanddel i det 21. århundrede, tilføjer bekvemmelighed, komfort, og endda skønhed til mange aspekter af hverdagen.

Materialets store alsidighed, som i øjeblikket hovedsageligt fremstilles af oliebiprodukter, har gjort polyurethan til go-to-plastic til en række produkter. I dag, mere end 16 millioner tons polyurethan produceres hvert år globalt.

"Meget få aspekter af vores liv berøres ikke af polyurethan, "afspejlede Phil Pienkos, en kemiker, der for nylig trak sig tilbage fra National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) efter næsten 40 års forskning.

Men Pienkos-der byggede en karriere efter at have undersøgt nye måder at producere biobaserede brændstoffer og materialer-sagde, at der er et stigende skub for at gentænke, hvordan polyurethan produceres.

"Nuværende metoder er i høj grad afhængige af giftige kemikalier og ikke-vedvarende råolie, "sagde han." Vi ville udvikle en ny plast med alle de nyttige egenskaber ved konventionel poly, men uden de dyre miljømæssige bivirkninger. "

Var det muligt? Resultater fra laboratoriet giver et rungende ja.

Gennem en ny kemi, der bruger ikke -toksiske ressourcer som linolie, fedtaffald, eller endda alger, Pienkos og hans NREL -kollega Tao Dong, en ekspert i kemiteknik, har udviklet en banebrydende metode til fremstilling af vedvarende polyurethan uden giftige forstadier.

Det er et gennembrud med potentiale til at grønne markedet for produkter lige fra fodtøj, til biler, til madrasser, og videre.

Men for at forstå den store vægt af præstationen, det er nyttigt at se tilbage på, hvordan det videnskabelige fremskridt opstod, en historie, der vandrer fra de kemiske grundlæggende principper for konventionel polyurethan, ind i algelaboratoriet, hvor en idé til en ny kemi først opstod, og snor sig til nye virksomhedspartnerskaber, der danner grundlag for en lovende fremtid for kommercialisering.

Et spørgsmål om kemi

Da polyurethan først blev kommercielt tilgængeligt i 1950'erne, det voksede hurtigt i popularitet til brug i mange produkter og applikationer. Det var ikke en lille del på grund af materialets dynamiske og afstembare egenskaber, samt tilgængeligheden og overkommeligheden af de oliebaserede komponenter, der bruges til fremstilling.

Gennem en smart kemisk proces ved hjælp af polyoler og isocyanater - de grundlæggende byggesten i konventionelle polyurethaner - kunne producenterne skræddersy deres formuleringer til at producere en fantastisk variation af polyurethanmaterialer, hver med unikke og nyttige egenskaber.

Fremstillet af en langkædet polyol, for eksempel, kan give fleksible skum til en pudeblød madras. En anden formulering kan give en rig væske, der, når det spredes på møbler, både beskytter og afslører trækornets iboende skønhed. Et tredje parti kan omfatte kuldioxid (CO 2 ) for at udvide materialet, fremstilling af et sprøjtbart skum, der tørrer til stiv og porøs isolering, perfekt til at holde varmen i et hjem.

"Det er det skønne ved isocyanat, "sagde Dong, når han reflekterede over konventionel polyurethan, "dens evne til at danne skum."

Men Dong sagde, at isocyanater medfører betydelige ulemper, også. Selvom disse kemikalier har hurtige reaktivitetshastigheder, gør dem meget fleksible til mange industriapplikationer, de er også meget giftige, og de er fremstillet af et endnu mere giftigt råstof, fosgen. Ved indånding, isocyanater kan føre til en række negative sundhedsvirkninger, som hud, øje, og irritation i halsen, astma, og andre alvorlige lungeproblemer.

"Hvis produkter, der indeholder konventionelle polyurethaner, brændes, disse isocyanater er flygtige og frigivet til atmosfæren, "Tilføjet Pienkos. Selv blot sprøjtning af polyurethan til brug som isolering, Pienkos sagde, kan aerosolisere isocyanat, kræver, at arbejdstagere tager omhyggelige forholdsregler for at beskytte deres helbred.

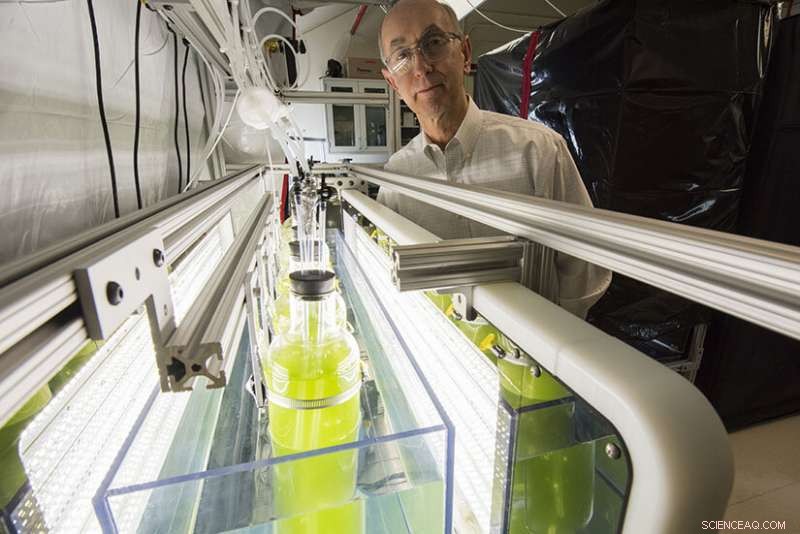

For nylig pensioneret, Phil Pienkos (billedet) grundlagde et nyt selskab, Polaris Renewables, to help accelerate the commercialization of the novel polyurethane, an idea that originally grew out of his algae biofuel research at NREL. Kredit:Dennis Schroeder, NREL

To try and tackle these and other issues—such as reliance on petrochemicals—scientists from labs around the world have begun looking for new ways to synthesize polyurethane using bio-based resources. But these efforts have largely had mixed results. Some lacked the performance needed for industry applications. Others were not completely renewable.

The challenge to improve polyurethane, derefter, remained ripe for innovation.

"We can do better than this, " thought Pienkos five years ago when he first encountered the predicament. Energized by the opportunity, he joined with Dong and Lieve Laurens, also of NREL, on a search for a better polyurethane chemistry.

Rethinking the Building Blocks of Polyurethane

The idea grew from a seemingly unrelated laboratory problem:lowering the cost of algae biofuels. As with many conventional petrochemical refining processes, biofuel refiners look for ways to use the coproducts of their processes as a source of revenue.

The question becomes much the same for algae biorefining. Can the waste lipids and amino acids from the process become ingredients for a prized recipe for polyurethane that is both renewable and nontoxic?

For Dong, answering the question at the basic chemical level was the easy part—of course they could. Scientists in the 1950s had shown it was possible to synthesize polyurethane from non-isocyanate pathways.

The real challenge, Dong said, was figuring out how to speed up that reaction to compete with conventional processes. He needed to produce polymers that performed at least as well as conventional materials, a major technical barrier to commercializing bio-based polyurethanes.

"The reactivity of the non-isocyanate, bio-based processes described in the literature is slower, " Dong explained. "So we needed to make sure we had reactivity comparable to conventional chemistry."

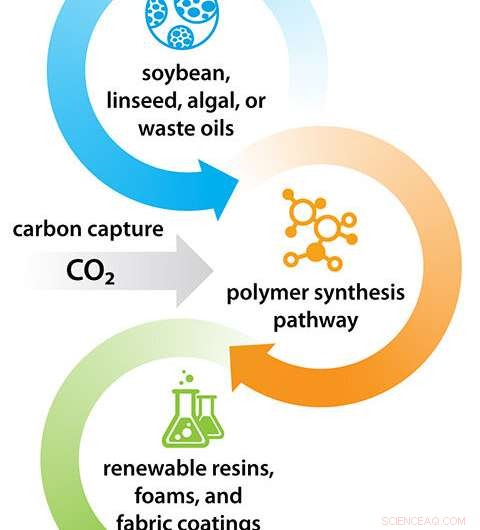

NREL's process overcomes the barrier by developing bio-based formulas through a clever chemical process. It begins with an epoxidation process, which prepares the base oil—anything from canola oil or linseed oil to algae or food waste—for further chemical reactions. By reacting these epoxidized fatty acids with CO 2 from the air or flue gas, carbonated monomers are produced. Endelig, Dong combines the carbonated monomers with diamines (derived from amino acids, another bio-based source) in a polymerization process that yields a material that cures into a resin—non-isocyanate polyurethane.

By replacing petroleum-based polyols with select natural oils, and toxic isocyanates with bio-based amino acids, Dong had managed to synthesize polymers with properties comparable to conventional polyurethane. Med andre ord, he had developed a viable renewable, nontoxic alternative to conventional polyurethane.

And the chemistry had an added environmental benefit, også.

"As much of 30% by weight of the final polymer is CO 2 , " Pienkos said, adding that the numbers are even more impressive when considering the CO 2 absorbed by the plants or algae used to create the oils and amino acids in the first place.

CO 2 , a ubiquitous greenhouse gas, is often considered an unfortunate waste product of various industrial processes, prompting many companies to look for ways to absorb it, eliminate it, or even put it to good use as a potential source of profit. By incorporating CO 2 into the very structure of their polyurethane, Pienkos and Dong had provided a pathway for boosting its value.

"That means less raw material per pound of polymer, lavere omkostninger, and a lower overall carbon footprint, " Pienkos continued. "It looks to us that this offers remarkable sustainability opportunities."

A Sought-After Renewable Solution Finds Its Commercial Feet

The next step was to see if the process could be commercialized, scaled up to meet the demands of the market.

The building blocks of poly—NREL's chemistry reacts natural oils with readily available carbon dioxide to produce renewable, nontoxic polyurethanes—a pathway for creating a variety of green materials and products. Kredit:National Renewable Energy Laboratory

Trods alt, renewable or not, polyurethane needs to demonstrate the properties that consumers expect from brand-name products. The process to create it must also match companies' manufacturing processes, allowing them to "drop in" the new material without prohibitively costly upgrades to facilities or equipment.

"That's why we need to work with industry partners, " Dong explained, "to make sure our research aligns with their manufacturing processes."

In the two short years since Pienkos and Dong first demonstrated the viability of producing fully renewable, nontoxic polyurethane, several companies have already contributed resources and research partnerships in the push for its commercialization.

A 2020 U.S. Department of Energy Technology Commercialization Fund award, for eksempel, brought in $730, 000 of federal funding to help develop the technology, as well as matching "in kind" cost share from the outdoor clothing company Patagonia, the mattress company Tempur Sealy, and a start-up biotechnology company called Algix.

And Pienkos says companies from other industries have shown preliminary interest, også. "These companies believe there is promise in this, " han sagde.

Their interest could partly be due to the tunability of Pienkos and Dong's approach, which lets them, much like conventional methods, create polymers that match industry standards.

"We've demonstrated that the chemistry is tunable, " Dong said. "We can control the final performance through our approach."

By controlling the epoxidation process or amount of carbonization, for eksempel, the process can be suited to meet the performance needs of a product. That may give the outsoles of a pair of running shoes enough flexibility and strength to endure many miles pounding into hot or cold asphalt. Or it may give a mattress a balance of stiffness and support.

"It's got regulation push. It's got market pull. It's got the potential to compete with non-renewables on the basis of cost. It's got a lower carbon footprint. It's got everything, " Pienkos said of the opportunities for commercialization. "This became the most exciting aspect of my career at NREL. Så, when I retired, I decided that I want to make this real. I want to see this technology actually make it into the marketplace."

After retiring last April, Pienkos went on to establish a company, Polaris Renewables, to help accelerate the commercialization of the novel polyurethane. Så, while he continues with his responsibilities as an NREL emeritus researcher, he is also doing outreach to industry to find additional corporate partners, especially in the fashion industry through the international sustainability initiative Fashion for Good.

"In the fashion industry, customers are demanding sustainability, " he explained. "They will pay something of a green premium if you can demonstrate a lower carbon footprint, better end of life disposition."

Ja, for both Pienkos and Dong, the breakthrough in renewable, nontoxic polyurethane has become more than an exciting scientific venture. It offers the world a pathway for products that leave a lighter mark on the environment.

"I think this is a great opportunity to solve the plastic pollution problem, " Dong said. "We need to save our environment, and part of that begins with making plastic renewable."

Pienkos, også, thinks that a commercial success in this venture could be a catalyst that spurs further growth and further success in bringing renewable, greener products to the market.

"This could be a success story for NREL, " he said. "A success here means a great deal to the world."

I dette tilfælde, success might be measured in more than the affordability of the production process or the carbon uptake of the polyurethane chemistry. In a world with NREL's renewable, nontoxic polyurethane, success might be something we can truly feel in the durability of our clothing, in the comfort our shoes provide, or in the rejuvenation we feel after sleeping on a memory foam mattress.

Sidste artikelSmart bulkplast reagerer på lys, temperatur og fugtighed

Næste artikelEt klarere overblik over, hvad der gør glas stift

Varme artikler

Varme artikler

-

Hvordan grønne alger samler deres enzymerAnne Sawyer har fået ny indsigt i grønmaskernes proteinmaskineri. Kredit:RUB, Kramer Forskere ved Ruhr-Universität Bochum har analyseret, hvordan grønne alger fremstiller komplekse komponenter af

Hvordan grønne alger samler deres enzymerAnne Sawyer har fået ny indsigt i grønmaskernes proteinmaskineri. Kredit:RUB, Kramer Forskere ved Ruhr-Universität Bochum har analyseret, hvordan grønne alger fremstiller komplekse komponenter af -

Kemikere er i stand til at fremkalde ensartet kiralitetKredit:CC0 Public Domain Chiralitet er en grundlæggende egenskab for mange organiske molekyler og betyder, at kemiske forbindelser ikke kun kan forekomme i én form, men også i to spejlbilledformer

Kemikere er i stand til at fremkalde ensartet kiralitetKredit:CC0 Public Domain Chiralitet er en grundlæggende egenskab for mange organiske molekyler og betyder, at kemiske forbindelser ikke kun kan forekomme i én form, men også i to spejlbilledformer -

Målretning af SARS-CoV-2-enzym med inhibitorerSkematisk af hovedproteasen af SARS CoV-2 (venstre), proteinrestnetværket af hovedproteasen i SARS CoV-2 (i midten), og en zoomet visning af området omkring bindingsstedet som detekteret af Estrada

Målretning af SARS-CoV-2-enzym med inhibitorerSkematisk af hovedproteasen af SARS CoV-2 (venstre), proteinrestnetværket af hovedproteasen i SARS CoV-2 (i midten), og en zoomet visning af området omkring bindingsstedet som detekteret af Estrada -

Sådan beregnes antallet af isomererIsomerer er forbindelser, der er identiske i formlen, men forskellige i struktur eller rumligt arrangement. De forekommer i hele naturen, men er af særlig interesse i organisk kemi - studiet af kul

Sådan beregnes antallet af isomererIsomerer er forbindelser, der er identiske i formlen, men forskellige i struktur eller rumligt arrangement. De forekommer i hele naturen, men er af særlig interesse i organisk kemi - studiet af kul

- NASA finder en antydning af et øje i den tropiske cyklon Pola

- Hydrogel forbedrer leveringen af lægemiddel mod kræft

- Hvor meget mikroplast er der i din vasketøjskurv?

- Ny undersøgelse analyserer globale miljøkonsekvenser af svækket handelsforhold mellem USA og Kina

- En miljøvenlig, lavprisløsning til spildevandsrensning

- Hvordan mennesker og robotter arbejder side om side i Amazon-opfyldelsescentre