Kunstig intelligens-forstærket journalistik giver et glimt af fremtiden for videnøkonomien

Robotter vil ikke holde pennene endnu, men de kan hjælpe folk med at udføre arbejdet. Kredit:Paul Fleet/Shutterstock.com

Ligesom robotter har transformeret hele dele af produktionsøkonomien, kunstig intelligens og automatisering ændrer nu informationsarbejdet, lader mennesker overføre kognitivt arbejde til computere. I journalistik, for eksempel, data mining-systemer advarer journalister om potentielle nyhedshistorier, mens nyhedsbots tilbyder nye måder for publikum at udforske information. Automatiserede skrivesystemer genererer økonomiske, sports- og valgdækning.

Et almindeligt spørgsmål, da disse intelligente teknologier infiltrerer forskellige industrier, er, hvordan arbejde og arbejdskraft vil blive påvirket. I dette tilfælde, hvem – eller hvad – vil lave journalistik i denne AI-forstærkede og automatiserede verden, og hvordan vil de gøre det?

De beviser, jeg har samlet i min nye bog "Automating the New:How Algorithms are Rewriting the Media" antyder, at fremtiden for AI-aktiveret journalistik stadig vil have masser af mennesker omkring sig. Imidlertid, jobs, roller og opgaver for disse mennesker vil udvikle sig og se lidt anderledes ud. Menneskeligt arbejde vil blive hybridiseret – blandet sammen med algoritmer – for at passe til AI's muligheder og imødekomme dets begrænsninger.

Forøgelse, ikke erstatter

Nogle skøn tyder på, at det nuværende niveau af AI-teknologi kun kan automatisere omkring 15 % af en journalists job og 9 % af en redaktørs job. Mennesker har stadig et forspring i forhold til ikke-Hollywood AI på flere nøgleområder, der er afgørende for journalistik, herunder kompleks kommunikation, ekspert tænkning, tilpasningsevne og kreativitet.

Indberetning, hører efter, reagerer og skubber tilbage, at forhandle med kilder, og så have kreativiteten til at sætte det sammen – AI kan ikke udføre nogen af disse uundværlige journalistiske opgaver. Det kan ofte øge menneskeligt arbejde, selvom, at hjælpe folk med at arbejde hurtigere eller med forbedret kvalitet. Og det kan skabe nye muligheder for at uddybe nyhedsdækningen og gøre den mere personlig for en individuel læser eller seer.

Newsroom arbejde har altid tilpasset sig bølger af ny teknologi, herunder fotografering, telefoner, computere – eller endda bare kopimaskinen. Journalister vil tilpasse sig arbejdet med kunstig intelligens, også. Som teknologi, det er allerede og vil fortsætte med at ændre nyhedsarbejde, ofte supplerende, men sjældent erstatter en uddannet journalist.

Nyt arbejde

Jeg har fundet ud af, at oftere end ikke, AI-teknologier ser ud til faktisk at skabe nye typer arbejde inden for journalistik.

Tag for eksempel Associated Press, som i 2017 introducerede brugen af computervision AI-teknikker til at mærke de tusindvis af nyhedsbilleder, den håndterer hver dag. Systemet kan mærke billeder med information om, hvad eller hvem der er på et billede, dens fotografiske stil, og om et billede afbilder grafisk vold.

Systemet giver billedredaktører mere tid til at tænke over, hvad de skal udgive, og frigør dem fra at bruge masser af tid på bare at mærke, hvad de har. Men at udvikle det tog et væld af arbejde, både redaktionelt og teknisk:Redaktører skulle finde ud af, hvad de skulle tagge, og om algoritmerne var op til opgaven, derefter udvikle nye testdatasæt for at evaluere ydeevnen. Da alt det var gjort, de skulle stadig overvåge systemet, manuel godkendelse af de foreslåede tags for hvert billede for at sikre høj nøjagtighed.

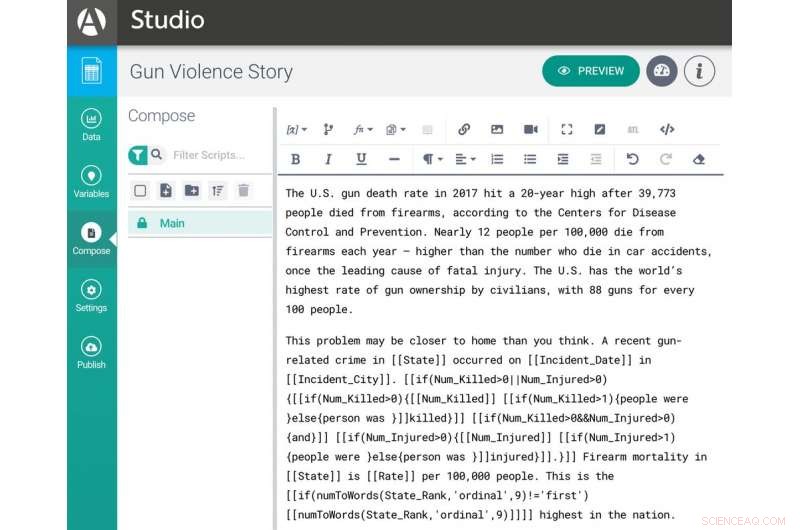

Arria Studio-brugergrænsefladen viser sammensætningen af en personlig historie om våbenvold. Kredit:Nicholas Diakopoulos skærmbillede af Arria Studio, CC BY-ND

Stuart Myles, AP-chefen, der fører tilsyn med projektet, fortalte mig, at det tog omkring 36 personmåneders arbejde, spread over a couple of years and more than a dozen editorial, technical and administrative staff. About a third of the work, he told me, involved journalistic expertise and judgment that is especially hard to automate. While some of the human supervision may be reduced in the future, he thinks that people will still need to do ongoing editorial work as the system evolves and expands.

Semi-automated content production

In the United Kingdom, the RADAR project semi-automatically pumps out around 8, 000 localized news articles per month. The system relies on a stable of six journalists who find government data sets tabulated by geographic area, identify interesting and newsworthy angles, and then develop those ideas into data-driven templates. The templates encode how to automatically tailor bits of the text to the geographic locations identified in the data. For eksempel, a story could talk about aging populations across Britain, and show readers in Luton how their community is changing, with different localized statistics for Bristol. The stories then go out by wire service to local media who choose which to publish.

The approach marries journalists and automation into an effective and productive process. The journalists use their expertise and communication skills to lay out options for storylines the data might follow. They also talk to sources to gather national context, and write the template. The automation then acts as a production assistant, adapting the text for different locations.

RADAR journalists use a tool called Arria Studio, which offers a glimpse of what writing automated content looks like in practice. It's really just a more complex interface for word processing. The author writes fragments of text controlled by data-driven if-then-else rules. For eksempel, in an earthquake report you might want a different adjective to talk about a quake that is magnitude 8 than one that is magnitude 3. So you'd have a rule like, IF magnitude> 7 THEN text ="strong earthquake, " ELSE IF magnitude <4 THEN text ="minor earthquake." Tools like Arria also contain linguistic functionality to automatically conjugate verbs or decline nouns, making it easier to work with bits of text that need to change based on data.

Authoring interfaces like Arria allow people to do what they're good at:logically structuring compelling storylines and crafting creative, nonrepetitive text. But they also require some new ways of thinking about writing. For eksempel, template writers need to approach a story with an understanding of what the available data could say—to imagine how the data could give rise to different angles and stories, and delineate the logic to drive those variations.

Supervision, management or what journalists might call "editing" of automated content systems are also increasingly occupying people in the newsroom. Maintaining quality and accuracy is of the utmost concern in journalism.

RADAR has developed a three-stage quality assurance process. Først, a journalist will read a sample of all of the articles produced. Then another journalist traces claims in the story back to their original data source. As a third check, an editor will go through the logic of the template to try to spot any errors or omissions. It's almost like the work a team of software engineers might do in debugging a script—and it's all work humans must do, to ensure the automation is doing its job accurately.

Developing human resources

Initiatives like those at the Associated Press and at RADAR demonstrate that AI and automation are far from destroying jobs in journalism. They're creating new work—as well as changing existing jobs. The journalists of tomorrow will need to be trained to design, update, tweak, validate, correct, supervise and generally maintain these systems. Many may need skills for working with data and formal logical thinking to act on that data. Fluency with the basics of computer programming wouldn't hurt either.

As these new jobs evolve, it will be important to ensure they're good jobs—that people don't just become cogs in a much larger machine process. Managers and designers of this new hybrid labor will need to consider the human concerns of autonomy, effectiveness and usability. But I'm optimistic that focusing on the human experience in these systems will allow journalists to flourish, and society to reap the rewards of speed, breadth of coverage and increased quality that AI and automation can offer.

Denne artikel er genudgivet fra The Conversation under en Creative Commons-licens. Læs den originale artikel.

Varme artikler

Varme artikler

-

Tysk Wikipedia blev mørklagt i protest mod EU's ophavsretsplanWikipedia logo. Wikipedias tysksprogede side er blevet mørklagt i protest mod et forslag om at ændre EUs ophavsretsregler. Besøgende på online-leksikonets tyske sektion blev torsdag mødt med en e

Tysk Wikipedia blev mørklagt i protest mod EU's ophavsretsplanWikipedia logo. Wikipedias tysksprogede side er blevet mørklagt i protest mod et forslag om at ændre EUs ophavsretsregler. Besøgende på online-leksikonets tyske sektion blev torsdag mødt med en e -

Implanterbar sensor nedbrydes, når dens anvendelighed ophørerEn fuldt biologisk nedbrydelig og strækbar belastnings- og tryksensor. en, Sensoren kan fastgøres til en sene til real-time helingsvurdering, gør det muligt at tilpasse rehabiliteringsprotokollen efte

Implanterbar sensor nedbrydes, når dens anvendelighed ophørerEn fuldt biologisk nedbrydelig og strækbar belastnings- og tryksensor. en, Sensoren kan fastgøres til en sene til real-time helingsvurdering, gør det muligt at tilpasse rehabiliteringsprotokollen efte -

Frankrig lover milliarder i kamp for at stoppe opstartsdrænetDen franske præsident Emmanuel Macron taler til tech-chefer og venturekapitalister ved en middag i Elysee-paladset i Paris tirsdag. Hvordan forhindrer du europæiske teknologivirksomheder i at flyt

Frankrig lover milliarder i kamp for at stoppe opstartsdrænetDen franske præsident Emmanuel Macron taler til tech-chefer og venturekapitalister ved en middag i Elysee-paladset i Paris tirsdag. Hvordan forhindrer du europæiske teknologivirksomheder i at flyt -

Forskere løser stor udfordring i masseproduktion af billige solcellerEn model af en perovskit solcelle, viser dets forskellige lag. Professor André D. Taylor har arbejdet på at løse fabrikationsudfordringer med perovskitceller. Kredit:Royal Society of Chemistry, Nanos

Forskere løser stor udfordring i masseproduktion af billige solcellerEn model af en perovskit solcelle, viser dets forskellige lag. Professor André D. Taylor har arbejdet på at løse fabrikationsudfordringer med perovskitceller. Kredit:Royal Society of Chemistry, Nanos

- Diorama-projekter på bærehabitater til Kids

- Big Tech mærker varmen, da USA bevæger sig for at beskytte forbrugerdata

- Forskere udvikler ny grafitbaseret sensorteknologi til bærbart medicinsk udstyr

- Familier med højt CO2-fodaftryk identificeret ved slik og restaurantmad, ikke højere kødforbrug

- Brug af kulnanorør til levering af lægemidler

- Skygger på månen - en fortælling om flygtig skønhed, mennesker og hybris