Transportpolitik i kinesiske byer

Ved hjælp af en ny metode, MITEI-forsker Joanna Moody og lektor Jinhua Zhao afslørede mønstre i udviklingstendenserne og transportpolitikkerne i Kinas 287 byer - inklusive Fengcheng, vist her - som kan hjælpe beslutningstagere med at lære af hinanden. Kredit:blake.thornberry/Flickr

I de seneste årtier har bybefolkningen i Kinas byer er vokset betydeligt, og stigende indkomster har ført til en hurtig udvidelse af bilejerskabet. Ja, Kina er nu verdens største marked for biler. Kombinationen af urbanisering og motorisering har ført til et presserende behov for transportpolitikker for at løse byproblemer såsom trængsel, luftforurening, og drivhusgasemissioner.

I de seneste tre år, et MIT-team ledet af Joanna Moody, forskningsprogramleder for MIT Energy Initiatives Mobility Systems Center, og Jinhua Zhao, Edward H. og Joyce Linde lektor i Institut for Bystudier og Planlægning (DUSP) og direktør for MIT's JTL Urban Mobility Lab, har undersøgt transportpolitik og politikudformning i Kina. "Det antages ofte, at transportpolitikken i Kina er dikteret af den nationale regering, " siger Zhao. "Men vi har set, at den nationale regering sætter mål og derefter tillader de enkelte byer at beslutte, hvilke politikker der skal implementeres for at nå disse mål."

Mange undersøgelser har undersøgt transportpolitikken i Kinas megabyer som Beijing og Shanghai, men få har fokuseret på de hundredvis af små og mellemstore byer i hele landet. Så humørsyg, Zhao, og deres team ønskede at overveje processen i disse oversete byer. I særdeleshed, de spurgte:hvordan beslutter kommunale ledere, hvilken transportpolitik de skal gennemføre, og kan de blive bedre i stand til at lære af hinandens erfaringer? Svarene på disse spørgsmål kan give vejledning til kommunale beslutningstagere, der forsøger at løse de forskellige transportrelaterede udfordringer, som deres byer står over for.

Svarene kunne også være med til at udfylde et hul i forskningslitteraturen. Antallet og mangfoldigheden af byer i hele Kina har gjort det udfordrende at udføre en systematisk undersøgelse af bytransportpolitik, men det emne er af stigende betydning. Som reaktion på lokal luftforurening og trafikpropper, nogle kinesiske byer vedtager nu politikker for at begrænse bilejerskab og -brug, og disse lokale politikker kan i sidste ende afgøre, om den hidtil usete vækst i det landsdækkende salg af private køretøjer vil fortsætte i de kommende årtier.

Politik læring

Transportpolitikere verden over drager fordel af en praksis kaldet policy-learning:Beslutningstagere i en by ser til andre byer for at se, hvilke politikker der har og ikke har været effektive. I Kina, Beijing og Shanghai ses normalt som trendsættere inden for innovativ transportpolitik, og kommunale ledere i andre kinesiske byer henvender sig til disse megabyer som rollemodeller.

Men er det en effektiv tilgang for dem? Trods alt, deres bymiljø og transportudfordringer er næsten helt sikkert helt anderledes. Ville det ikke være bedre, hvis de kiggede efter "peer"-byer, som de har mere til fælles med?

Humørfuld, Zhao, og deres DUSP-kolleger – postdoc Shenhao Wang og kandidatstuderende Jungwoo Chun og Xuenan Ni, alle i JTL Urban Mobility Lab – antydede en alternativ ramme for politiklæring, hvor byer, der deler fælles urbaniserings- og motoriseringshistorier, ville dele deres politikviden. En lignende udvikling af byrum og rejsemønstre kan føre til de samme transportudfordringer, og derfor til lignende behov for transportpolitikker.

For at teste deres hypotese, forskerne skulle besvare to spørgsmål. At begynde, de havde brug for at vide, om kinesiske byer har et begrænset antal fælles urbaniserings- og motoriseringshistorier. Hvis de grupperede de 287 byer i Kina baseret på disse historier, ville de ende med et moderat lille antal meningsfulde grupper af jævnaldrende byer? Og for det andet, ville byerne i hver gruppe have lignende transportpolitikker og prioriteter?

Gruppering af byerne

Byer i Kina er ofte grupperet i tre "lag" baseret på politisk administration, eller de typer af jurisdiktionsroller byerne spiller. Niveau 1 inkluderer Beijing, Shanghai, og to andre byer, der har samme politiske beføjelser som provinser. Tier 2 omfatter omkring 20 provinshovedstæder. The remaining cities—some 260 of them—all fall into Tier 3. These groupings are not necessarily relevant to the cities' local urban and transportation conditions.

Moody, Zhao, and their colleagues instead wanted to sort the 287 cities based on their urbanization and motorization histories. Heldigvis, they had relatively easy access to the data they needed. Hvert år, the Chinese government requires each city to report well-defined statistics on a variety of measures and to make them public.

Among those measures, the researchers chose four indicators of urbanization—gross domestic product per capita, total urban population, urban population density, and road area per capita—and four indicators of motorization—the number of automobiles, taxis, busser, and subway lines per capita. They compiled those data from 2001 to 2014 for each of the 287 cities.

The next step was to sort the cities into groups based on those historical datasets—a task they accomplished using a clustering algorithm. For the algorithm to work well, they needed to select parameters that would summarize trends in the time series data for each indicator in each city. They found that they could summarize the 14-year change in each indicator using the mean value and two additional variables:the slope of change over time and the rate at which the slope changes (the acceleration).

Based on those data, the clustering algorithm examined different possible numbers of groupings, and four gave the best outcome in terms of the cities' urbanization and motorization histories. "With four groups, the cities were most similar within each cluster and most different across the clusters, " says Moody. "Adding more groups gave no additional benefit."

The four groups of similar cities are as follows:

- Cluster 1:23 large, dense, wealthy megacities that have urban rail systems and high overall mobility levels over all modes, including buses, taxis, and private cars. This cluster encompasses most of the government's Tier 1 and Tier 2 cities, while the Tier 3 cities are distributed among Clusters 2, 3, and 4.

- Cluster 2:41 wealthy cities that don't have urban rail and therefore are more sprawling, have lower population density, and have auto-oriented travel patterns.

- Cluster 3:134 medium-wealth cities that have a low-density urban form and moderate mobility fairly spread across different modes, with limited but emerging car use.

- Cluster 4:89 low-income cities that have generally lower levels of mobility, with some public transit buses but not many roads. Because people usually walk, these cities are concentrated in terms of density and development.

City clusters and policy priorities

The researchers' next task was to determine whether the cities within a given cluster have transportation policy priorities that are similar to each other—and also different from those of cities in the other clusters. With no quantitative data to analyze, the researchers needed to look for such patterns using a different approach.

Først, they selected 44 cities at random (with the stipulation that at least 10 percent of the cities in each cluster had to be represented). They then downloaded the 2017 mayoral report from each of the 44 cities.

Those reports highlight the main policy initiatives and directions of the city in the past year, so they include all types of policymaking. To identify the transportation-oriented sections of the reports, the researchers performed keyword searches on terms such as transportation, road, car, bus, and public transit. They extracted any sections highlighting transportation initiatives and manually labeled each of the text segments with one of 21 policy types. They then created a spreadsheet organizing the cities into the four clusters. Endelig, they examined the outcome to see whether there were clear patterns within and across clusters in terms of the types of policies they prioritize.

"We found strikingly clear patterns in the types of transportation policies adopted within city clusters and clear differences across clusters, " says Moody. "That reinforced our hypothesis that different motorization and urbanization trajectories would be reflected in very different policy priorities."

Here are some highlights of the policy priorities within the clusters:

The cities in Cluster 1 have urban rail systems and are starting to consider policies around them. For eksempel, how can they better connect their rail systems with other transportation modes—for instance, by taking steps to integrate them with buses or with walking infrastructure? How can they plan their land use and urban development to be more transit-oriented, such as by providing mixed-use development around the existing rail network?

Cluster 2 cities are building urban rail systems, but they're generally not yet thinking about other policies that can come with rail development. They could learn from Cluster 1 cities about other factors to take into account at the outset. For eksempel, they could develop their urban rail with issues of multi-modality and of transit-oriented development in mind.

In Cluster 3 cities, policies tend to emphasize electrifying buses and providing improved and expanded bus service. In these cities with no rail networks, the focus is on making buses work better.

Cluster 4 cities are still focused on road development, even within their urban areas. Policy priorities often emphasize connecting the urban core to rural areas and to adjacent cities—steps that will give their populations access to the region as a whole, expanding the opportunities available to them.

Benefits of a "mixed method" approach

Results of the researchers' analysis thus support their initial hypothesis. "Different urbanization and motorization trends that we captured in the clustering analysis are reflective of very different transportation priorities, " says Moody. "That match means we can use this approach for further policymaking analysis."

At the outset, she viewed their study as a "proof of concept" for performing transportation policy studies using a mixed-method approach. Mixed-method research involves a blending of quantitative and qualitative approaches. In their case, the former was the mathematical analysis of time series data, and the latter was the in-depth review of city government reports to identify transportation policy priorities. "Mixed-method research is a growing area of interest, and it's a powerful and valuable tool, " says Moody.

She did, imidlertid, find the experience of combining the quantitative and qualitative work challenging. "There weren't many examples of people doing something similar, and that meant that we had to make sure that our quantitative work was defensible, that our qualitative work was defensible, and that the combination of them was defensible and meaningful, " hun siger.

The results of their work confirm that their novel analytical framework could be used in other large, rapidly developing countries with heterogeneous urban areas. "It's probable that if you were to do this type of analysis for cities in, say, Indien, you might get a different number of city types, and those city types could be very different from what we got in China, " says Moody. Regardless of the setting, the capabilities provided by this kind of mixed method framework should prove increasingly important as more and more cities around the world begin innovating and learning from one another how to shape sustainable urban transportation systems.

Denne historie er genudgivet med tilladelse fra MIT News (web.mit.edu/newsoffice/), et populært websted, der dækker nyheder om MIT-forskning, innovation og undervisning.

Varme artikler

Varme artikler

-

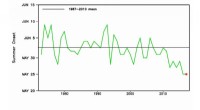

Menneskelige aktiviteter øger risikoen for, at sommeren starter tidligt i SydkoreaSommer startdato i Sydkorea i løbet af 1973 - 2017. Den tidligste debut blev registreret i 2017 med rekordhøj majstemperatur. Kredit:ResearchSEA Computerklimamodeller tyder på, at menneskelige akt

Menneskelige aktiviteter øger risikoen for, at sommeren starter tidligt i SydkoreaSommer startdato i Sydkorea i løbet af 1973 - 2017. Den tidligste debut blev registreret i 2017 med rekordhøj majstemperatur. Kredit:ResearchSEA Computerklimamodeller tyder på, at menneskelige akt -

Regn i slutningen af oktober kunne dæmpe skovbrande og hjælpe med tørke, siger prognosemændKredit:Unsplash/CC0 Public Domain En vådere vejrudsigt end gennemsnittet for slutningen af oktober kan dæmpe skovbrande, der brænder i det nordlige Californien og hjælpe med at lette tørkeforhol

Regn i slutningen af oktober kunne dæmpe skovbrande og hjælpe med tørke, siger prognosemændKredit:Unsplash/CC0 Public Domain En vådere vejrudsigt end gennemsnittet for slutningen af oktober kan dæmpe skovbrande, der brænder i det nordlige Californien og hjælpe med at lette tørkeforhol -

Indonesiske skovbrande bringer 10 millioner børn i fare:FNIndonesiske børn får en dosis ilt fra en frivillig fra Røde Kors. UNICEF siger, at skovbrandene udsætter næsten 10 millioner børn i fare fra den giftige luft Luftforurening fra indonesiske skovbra

Indonesiske skovbrande bringer 10 millioner børn i fare:FNIndonesiske børn får en dosis ilt fra en frivillig fra Røde Kors. UNICEF siger, at skovbrandene udsætter næsten 10 millioner børn i fare fra den giftige luft Luftforurening fra indonesiske skovbra -

Varm vind:Ny indsigt i, hvad der svækker antarktiske ishylderSmeltevandsbassiner på Larsen C ishylde i Antarktis. Kredit:Jenny Turton (British Antarctic Survey) Ny forskning beskriver for første gang den rolle, der varmer, tør vind spiller ind på at påvirke

Varm vind:Ny indsigt i, hvad der svækker antarktiske ishylderSmeltevandsbassiner på Larsen C ishylde i Antarktis. Kredit:Jenny Turton (British Antarctic Survey) Ny forskning beskriver for første gang den rolle, der varmer, tør vind spiller ind på at påvirke

- Dyb læring forlænger billeddybden og fremskynder genopbygning af hologrammer

- Forskere lokker til partikler til dannelse af hvirvler ved hjælp af magnetfelter

- Når alle arbejder på afstand, kommunikation og samarbejde lider, undersøgelse finder

- NASAs sigter mod supersoniske jetfly fri for det irriterende soniske bom

- Et signalforøgelse til molekylær mikroskopi

- Sådan Multipliceres Vectors