Stillehavsrotter spor 2, 000 års menneskelig påvirkning på øens økosystemer

Agakauitai Island i Gambier Archipelago (Mangareva). Kredit:Jillian A. Swift

Kemisk analyse af resterne af rotter fra arkæologiske steder, der spænder over de sidste 2000 år på tre polynesiske ø-systemer, har vist menneskers indvirkning på lokale miljøer. Analysen af et internationalt hold af videnskabsmænd gjorde det muligt for forskerne at rekonstruere rotternes kost – og gennem dem, ændringer foretaget af mennesker til lokale økosystemer, herunder indfødte arters udryddelse og ændringer i fødevæv og jordens næringsstoffer.

Jorden er gået ind i en ny geologisk epoke kaldet antropocæn, en æra, hvor mennesker skaber betydningsfulde, varig forandring af planeten. Mens de fleste geologer og økologer placerer oprindelsen af denne æra i de sidste 50 til 300 år, mange arkæologer har hævdet, at vidtrækkende menneskelige indvirkninger på geologi, biodiversitet, og klima strækker sig årtusinder tilbage i fortiden.

Gamle menneskelige påvirkninger er ofte vanskelige at identificere og måle sammenlignet med dem, der sker i dag eller i nyere historie. En ny undersøgelse offentliggjort i Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences af forskere ved Max Planck Institute for Science of Human History i Jena og University of California, Berkeley fremmer en ny metode til at opdage og kvantificere menneskelige transformationer af lokale økosystemer i fortiden. Ved at bruge avancerede metoder, forskere søgte efter spor om tidligere menneskelige ændringer af øens økosystemer fra en usædvanlig kilde - knoglerne fra forlængst døde rotter, der er genvundet fra arkæologiske steder.

En af de mest ambitiøse og udbredte migrationer i menneskehedens historie begyndte ca. 3000 år siden, da folk begyndte at sejle over Stillehavet – ud over den synlige horisont – på jagt efter nye øer. For omkring 1000 år siden, mennesker havde nået selv de fjerneste kyster i Stillehavet, inklusive grænserne for den polynesiske region:øerne Hawaii, Rapa Nui (Påskeøen) og Aotearoa (New Zealand). Uden at vide, hvad de ville møde i disse nye lande, tidlige rejser medbragte en række velkendte planter og dyr, herunder afgrøder som taro, brødfrugt, og yams, og dyr, inklusive grisen, hund, og kylling. Blandt de nyankomne var også stillehavsrotten (Rattus exulans), som blev båret til næsten alle polynesiske øer på disse tidlige rejser, måske med vilje som mad, eller lige så sandsynligt, som en skjult "bropassager" ombord på langdistancefartskanoer.

Udgravning af 'Kitchen Cave' Rockshelter (KAM-1) i gang. Kamaka Island, Gambier-øgruppen (Mangareva). Kredit:Patrick V. Kirch

Rottens ankomst havde en dyb indvirkning på øens økosystemer. Stillehavsrotter jagede lokale havfugle og spiste frø fra endemiske træarter. Vigtigere, kommensale dyr som stillehavsrotten indtager en unik position i menneskets økosystemer. Ligesom husdyr, de tilbringer det meste af deres tid i og omkring menneskelige bosættelser, overlever på fødevareressourcer produceret eller akkumuleret af mennesker. Imidlertid, i modsætning til deres hjemlige kolleger, disse kommensale arter forvaltes ikke direkte af mennesker. Deres kost giver således indsigt i den mad, der er tilgængelig i menneskelige bosættelser, såvel som ændringer i øens økosystemer mere bredt.

Men hvordan rekonstruerer man kosten af gamle rotter? At gøre dette, the researchers examined the biochemical composition of rat bones recovered from archaeological sites across three Polynesian island systems. Carbon isotope analysis of proteins preserved in archaeological bone indicates the types of plants consumed, while nitrogen isotopes point to the position of the animal in a food web. Nitrogen isotopes are also sensitive to humidity, soil quality, and land use. This study examined the carbon and nitrogen isotopes of archaeological Pacific rat remains across seven islands in the Pacific, spanning roughly 2000 years of human occupation. The researchers' results demonstrate the impacts of processes like human forest clearance, hunting of native avifauna (in particular land birds and seabirds) and the development of new, agricultural landscapes on food webs and resource availability.

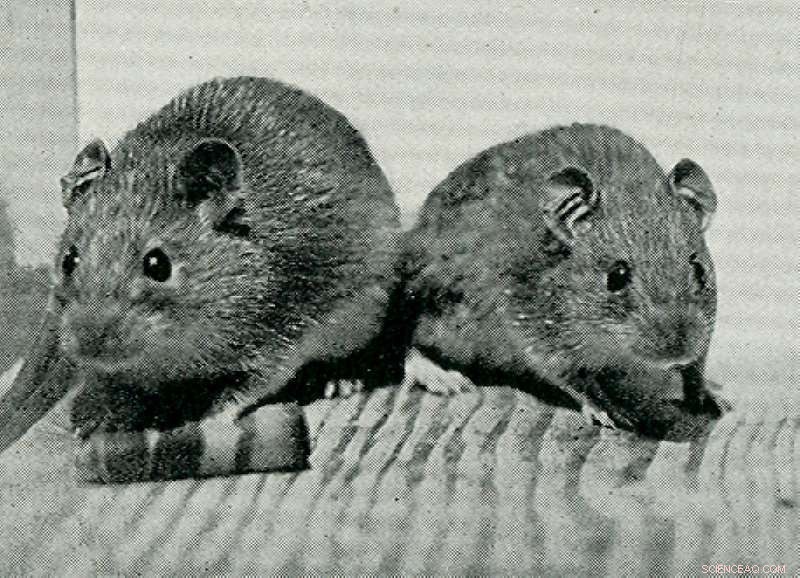

Pacific rats ( Rattus exulans ). Credit:Photo taken by John Stokes (Bernice P. Bishop Museum), and courtesy of Patrick V. Kirch.

A near-universal pattern of changing rat bone nitrogen isotope values through time was linked to native species extinctions and changes in soil nutrient cycling after people arrived on the islands. In addition, significant changes in both carbon and nitrogen isotopes correspond with agricultural expansion, human site activity, and subsistence choices. "We have many strong lines of archaeological evidence for humans modifying past ecosystems as far back as the Late Pleistocene, " says lead author Jillian Swift, of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. "The challenge is in finding datasets that can quantify these changes in ways that allow us to compare archaeological and modern datasets to help predict what impacts human modifications will have on ecosystems in the future."

Prof. Patrick V. Kirch of the University of California, Berkeley, who supervised the study and led excavations on Tikopia and Mangareva, remarked that "the new isotopic methods allow us to quantify the ways in which human actions have fundamentally changed island ecosystems. I hardly dreamed this might be possible back in the 1970s when I excavated the sites on Tikopia Island."

"Commensal species, such as the Pacific rat, are often forgotten about in archaeological assemblages. Although they are seen as less glamorous 'stowaways' when compared to domesticated animals, they offer an unparalleled opportunity to look at the new ecologies and landscapes created by our species as it expanded across the face of the planet, " added Patrick Roberts of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, a co-author on the paper. "The development and use of stable isotope analysis of commensal species raises the possibility of tracking the process of human environment modification, not just in the Pacific, but around the world where they are found in association with human land use."

The study highlights the extraordinary degree to which people in the past were able to modify ecosystems. "Studies like this clearly highlight the human capacity for 'ecosystem engineering, '" notes Nicole Boivin, coauthor of the study and Director of the Department of Archaeology at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. "We clearly have long had the capability as a species of massively transforming the world around us. What's new today is our ability to understand, measure, and alleviate these impacts."

Sidste artikelIndvandrere og dårligt stillede børn har mest gavn af tidlig børnepasning

Næste artikelHatte på til påskeøens statuer

Varme artikler

Varme artikler

-

Vælgere med højest COVID-19 risikerer mere tilbøjelige til at afgive brevstemme, viser undersøge…Kredit:Unsplash/CC0 Public Domain Vælgere med den højeste risiko for at lide af COVID-19s værste virkninger siger, at de er mere tilbøjelige til at afgive brevstemme i november, selvom mange af de

Vælgere med højest COVID-19 risikerer mere tilbøjelige til at afgive brevstemme, viser undersøge…Kredit:Unsplash/CC0 Public Domain Vælgere med den højeste risiko for at lide af COVID-19s værste virkninger siger, at de er mere tilbøjelige til at afgive brevstemme i november, selvom mange af de -

3 måder at tilskynde mennesker med handicap til at være involveret i at lede katastrofeberedskabDe Forenede Nationer (FN) har opfordret til at styrke personer med handicap, så de ikke kun er involveret, men også kan føre an i katastrofehåndtering. Deres ledelse er afgørende for at sikre, at enhv

3 måder at tilskynde mennesker med handicap til at være involveret i at lede katastrofeberedskabDe Forenede Nationer (FN) har opfordret til at styrke personer med handicap, så de ikke kun er involveret, men også kan føre an i katastrofehåndtering. Deres ledelse er afgørende for at sikre, at enhv -

Videregående uddannelse var allerede moden til at blive forstyrret - dengang, COVID-19 sketeKredit:CC0 Public Domain Tilbage i foråret, da COVID-19 dukkede op rundt om i verden og førte til omfattende nedlukninger, skoler på alle niveauer måtte hurtigt tilpasse sig. Klasserne gik online.

Videregående uddannelse var allerede moden til at blive forstyrret - dengang, COVID-19 sketeKredit:CC0 Public Domain Tilbage i foråret, da COVID-19 dukkede op rundt om i verden og førte til omfattende nedlukninger, skoler på alle niveauer måtte hurtigt tilpasse sig. Klasserne gik online. -

Neandertaler-værktøjsfremstillingsprocessen kan have været enklere end tidligere antagetForsøgsopstilling til fremstilling af birketjære. Forskere brændte birkebark nær flade overflader, som neandertalere ville have brugt. Kredit:Universitetet i Tübingen, Matthias Blessing Neandertal

Neandertaler-værktøjsfremstillingsprocessen kan have været enklere end tidligere antagetForsøgsopstilling til fremstilling af birketjære. Forskere brændte birkebark nær flade overflader, som neandertalere ville have brugt. Kredit:Universitetet i Tübingen, Matthias Blessing Neandertal

- 10 måder dyr forudsiger angiveligt vejret

- Massiv exoplanet opdaget ved hjælp af gravitationel mikrolinsemetode

- Over en fjerdedel af mennesker siger, at deres liv er meget anderledes nu sammenlignet med før COVI…

- Enestående vækst på kollegiets arbejdsmarked

- At se et bionisk øje på medicinhorisonten

- Shoppers mobilitetsvaner:Detailhandlere overvurderer bilbrug