Fiskekampe:Storbritannien har en lang historie med at forbyde adgang til kystnære farvande

En Brixham-trawler fra det 19. århundrede af William Adolphus Knell. Kredit:National Maritime Museum/Wikipedia

De britiske både var i undertal med omkring otte til én af franskmændene. Inden længe var der kollisioner og projektiler blev kastet. Briterne blev tvunget til at trække sig tilbage, vender tilbage til havn med knuste ruder, men heldigvis ingen skader.

Konflikten bag denne træfning mellem britiske og franske fiskere i Seinebugten i slutningen af august 2018 blev hurtigt døbt "kamuslingekrigen" i pressen. Franskmændene havde forsøgt at forhindre, at de britiske kammuslingudgravere lovligt fiskede bedene i franske nationale farvande. Men hændelsen afslørede spændinger, der har ulmet i mange år.

Under Den Europæiske Unions fælles fiskeripolitik (CFP), de britiske fiskere havde lovlig ret til at fiske i disse farvande, ligesom alle både fra et EU-medlemsland. Komplikationen kom fra en fransk regulering, der forhindrede lokale både i at fiske i disse farvande mellem 16. maj og 30. september hvert år, for at give bestandene mulighed for at komme sig efter den årlige høst. Men under den fælles fiskeripolitik, et EU-land har ingen bemyndigelse til at forhindre en anden medlemslands flåde i at fiske dens farvande.

Denne finurlighed i den fælles fiskeripolitik gjorde, at de franske fiskere ikke var i stand til at mudre efter kammuslinger før den 1. oktober, og tvunget til at stå forbi og se på, mens flåder fra andre lande høstede, hvad de så som en fransk ressource fra franske farvande. Da de britiske både ankom, de franske fiskere påtog sig rollen som vogtere af deres ressource, handlinger, som de mente var berettigede, men af den britiske fiskeindustri blev betragtet som ulovlige.

Denne hændelse i et lille hjørne af et fælles EU-hav blev afgjort inden for få uger takket være en ny aftale om, hvordan de to lande ville dele kammuslinghøsten. Men de underliggende spændinger, som den fælles fiskeripolitik har skabt over deling af nationale ressourcer, går meget dybere, med en følelse af, at reglerne ikke tillader en rimelig udnyttelse af havene.

Denne følelse af uretfærdighed kom tydeligvis til udtryk i den rolle, som fiskeriet spillede i Storbritanniens beslutning om at forlade EU. Kampagner lovede, at "at tage kontrollen tilbage" over britiske farvande ville sætte landet i stand til at genoplive sin længe faldende fiskeindustri og de samfund, der er afhængige af den.

Men uanset hvilken indflydelse den fælles fiskeripolitik har haft på Storbritanniens fiskere, deres fremtid efter Brexit afhænger meget af enhver fremtidig handelsaftale, som regeringen forhandler med EU. Og historien om, hvordan Storbritannien har reageret på konflikter om fiskerettigheder, der er langt større end kammuslingekrigen, lover ikke godt for industrien.

Starten på tilbagegangen

Forskning i fiskeriaktivitet viser, at den britiske fiskeriindustris tilbagegang begyndte længe før oprettelsen af nogen europæisk fiskeripolitik. Faktisk, dens ultimative oprindelse kan spores til en overraskende kilde:jernbanernes udvidelse i slutningen af det 19. århundrede.

Trawling, under sejlets magt, havde eksisteret i mere end 500 år. Men uden køling, fisk kunne kun leveres til salg til områder tæt på havnene. Jernbanenettets komme betød, at fisk kunne transporteres ind i landet til store byer.

For yderligere at imødekomme denne voksende efterspørgsel, damptrawlere begyndte at erstatte sejltrawlere fra 1880'erne og frem. Kraften fra disse dampfartøjer øgede omfanget af trawlfiskeri og gjorde det muligt for dem at trawle længere og længere væk fra havnen, mens de bugserede større net. Britiske damptrawlere vovede sig længere væk fra Storbritannien på jagt efter fisk, hvor fiskepladserne udvider sig til områder så langt som til Grønland, Nordnorge og Barentshavet, Island og Færøerne.

Men allerede i 1885 der blev rejst bekymring for, at dette fremskridt inden for teknologi havde en negativ indvirkning på både fiskebestande og deres levesteder. Beviser fra registreringer af fiskeriaktivitet viser, at denne forbedring af teknologien og den øgede størrelse af fiskerflåden var helt bagved stigningen i landinger.

Det fiskeriboom, som jernbanerne havde udløst, viste sig uholdbart, og det resulterende overfiskeri ville i sidste ende sende industrien ud i en langsigtet nedtur. Efter årtier med mere og mere fiskeri, landgange begyndte til sidst at falde efter Anden Verdenskrig, en tendens, der fortsatte gennem anden halvdel af det 20. århundrede og ind i det nye årtusinde.

For at kompensere, flådens størrelse og kraft fortsatte med at stige, efterhånden som der krævedes en større indsats for at fange stadigt færre fisk. Fra slutningen af 1950'erne, mængden af landede fisk pr. effektenhed faldt hurtigere end fiskelandinger, efterhånden som flåden fortsatte med at bruge flere og flere kræfter på at opretholde fangststørrelsen. Imidlertid, denne indsats var helt forgæves, og i 1980 var fangsterne faldet til det laveste punkt i et århundrede.

Islands Odinn og HMS Scylla støder sammen i Nordatlanten under 'Tredje Torskekrig' i 1970'erne. Kredit:Isaac Newton/www.hmsbacchante.co.uk

Torskekrige

Overfiskeri var ikke den eneste årsag til tilbagegang, imidlertid. De faldende fiskebestande kombineret med forbedringerne i flådens rækkevidde og kraft i efterkrigsårene fik Storbritanniens fiskere til at søge nye farvande, med flere både, der flytter længere væk fra Storbritannien for at fange nok fisk til at imødekomme den indenlandske efterspørgsel. Og denne langdistancetrawling bragte den britiske flåde i konflikt med Island.

Britiske fiskere havde fisket i disse farvande fra det 15. århundrede. Imidlertid, Islands fiskeindustri begyndte at ærgre sig over dette, da damptrawlerne begyndte at fiske ud for Island i slutningen af det 19. århundrede. Det førte til beskyldninger om, at britiske trawlere beskadigede fiskepladserne og udtømte bestandene. I 1952, Island erklærede en fire-mile zone omkring deres land for at stoppe overdreven udenlandsk fiskeri, selvom fisk ikke holder sig til menneskeskabte grænser, og bestandene kan stadig være udtømte uden for denne zone. Islands beslutning trak et svar fra Storbritannien, som forbød import af islandsk fisk. Som et stort eksportmarked for Islands vigtigste industri håbede de, at dette ville bringe dem til forhandlingsbordet.

I 1958, på baggrund af mislykket diplomati, Island udvidede denne zone til 12 sømil og forbød udenlandske flåder at fiske i disse farvande, i strid med international lov. Det førte til den første af det, der blev kendt som Cod Wars - en handling i tre faser, der varede næsten 20 år.

Under den første torskekrig, Royal Navy fregatter ledsagede den britiske flåde ind i Islands udelukkelseszone for at fortsætte deres fiskeri. Et spil kat-og-mus opstod mellem de islandske kystvagtfartøjer og de britiske trawlere. Som svar på forsøg på at gribe dem, trawlerne ramte kystvagtskibene, og kystvagten truede med at åbne ild, selvom større hændelser blev undgået.

I 1961, de to lande kom til sidst til en aftale, der tillod Island at beholde sin 12-mile zone. Til gengæld, Storbritannien fik betinget adgang til disse farvande.

I 1972, imidlertid, overfiskeri uden for denne grænse var blevet værre, og Island udvidede sin eksklusive zone til 50 sømil og derefter tre år senere, til 200 miles. Begge disse træk førte til flere sammenstød mellem islandske trawlere og Royal Navy-eskorteskibe, henholdsvis døbt den anden og tredje Torskekrig.

Islandske kystvagtfartøjer bugserede anordninger designet til at skære ståltrawltrådene (hawsers) fra de britiske trawlere - og fartøjer fra alle sider var involveret i bevidste kollisioner. Selvom disse sammenstød hovedsageligt var blodløse, a British fisher was seriously injured when he was hit by a severed hawser and an Icelandic engineer died while repairing damage to a trawler that had clashed with a Royal Navy frigate.

In January 1976, British naval frigate HMS Andromeda collided with Thor, an Icelandic gunboat, which also sustained a hole in its hull. While British officials called the collision a "deliberate attack", the Icelandic Coastguard accused the Andomeda of ramming Thor by overtaking and then changing course. Eventually NATO intervened and another agreement was reached in May 1976 over UK access and catch limits. This agreement gave 30 vessels access to Iceland's waters for six months.

NATO's involvement in the dispute had little to do with fisheries and a large amount to do with the Cold War. Iceland was a member of NATO, and therefore aligned to the US, with a substantial US military presence in Iceland at the time. Iceland believed that NATO should intervene in the dispute but it had up until that point resisted. Popular feeling against NATO grew in Iceland and the US became concerned that this strategically important island nation – which allowed control of the Greenland Iceland UK (GIUK) gap, an anti-submarine choke point – could leave NATO and worse, align itself with the Soviets.

Amid protests at the US military base in Iceland demanding the expulsion of the Americans, and growing calls from Icelandic politicians that they should leave NATO, the US put pressure on the British to concede in order to protect the NATO alliance. The agreement brought to an end more than 500 years of unrestricted British fishing in these waters.

The loss of these Atlantic fishing grounds cost 1, 500 jobs in the home ports of the UK's distant water fleet, concentrated around Scotland and the north-east of England, with many more jobs lost in shore-based support industries. This had a significant negative impact on the fishing communities in these areas.

The UK also established its own 200-mile limit in response to Iceland's exclusion zone. These limits were eventually incorporated in the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, giving similar rights to every sovereign nation. The creation of these "exclusive economic zones" (EEZ) was the first time that the international community had recognised that nations could own all of the resources that existed within the seas that surrounded them and exclude other nations from exploiting these resources.

The UK now owned the rights to the 200-mile zone around its islands, which contained some of the richest fishing grounds in Europe but up until this point the principle of "open seas" had existed, with Britain its most vocal champion. Fishing nations, had fished the high seas within 200 miles of their own and others coasts for centuries and now were restricted to their own.

British trawler Coventry City passes Icelandic Coastguard patrol vessel Albert off the Westfjords in 1958 during the first Cod War. Credit:Kjallakr/Wikipedia

Economic trade offs

Britain's Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), imidlertid, wasn't that exclusive.

On joining the European Economic Community (the forerunner to the EU) in 1972, the UK had agreed to a policy of sharing access to its waters with all member states, and gaining access to the waters of other countries in return. The UN convention effectively gave the EEC one giant EEZ.

The UK government was willing to enter into the agreement as fisheries were one part of overall negotiations that would allow the UK to export goods and services to the European continent with significantly reduced trade barriers.

Although the fishing industry is of high local importance to fishing communities, it is relatively unimportant to the UK economy as a whole. I 2016 the UK fishing industry (which includes the catching sector and all associated industries) was valued at £1.6 billion, against £1.76 trillion for the UK economy as a whole – or just under 1%. The UK's trade with the EU, both import and export, stands at £615 billion a year in comparison.

Enter the Common Fisheries Policy

I 1983, the Common Fisheries Policy was adopted, introducing management of European waters by giving each state a quota for what it could catch, based on a pre-determined percentage of total fishing opportunities. This was known as "relative stability" and was based on each country's historic fishing activity before 1983, which still determines how quotas are allocated today.

The formula that the EEC adopted, based on historic catches, is one of most contentious parts of the CFP for the UK. Many fishers have stories of the years running up to 1983, where foreign vessels increased their fishing activity in UK waters in order to secure a larger share of these fish in perpetuity. Although there is little evidence to support these views, it demonstrates the level of distrust in both the system, and foreign fishers, from the outset.

Som resultat, only 32% of fish caught in the UK EEZ today is caught by UK boats, with most of the remainder taken by vessels from other EU states, Norway and the Faroe Islands (who have also joined the CFP). Derfor, non-UK vessels catch the remaining 68%, about 700, 000 tonnes, of fish a year in the UK EEZ.In return, the UK fleet lands about 92, 000 tonnes a year from other EU countries' waters.

Joining the CFP did not cause a decline in UK fish landings. Imidlertid, i sine tidlige dage, it did nothing to stop it. Fish landings continued to decline – and along with this, the industry itself contracted, using improved technology to offset the decline in stocks. Through the 1980s and into the early part of this century the imbalance – enshrined in the relative stability measure of the CFP – has led to the view that the CFP doesn't work in the UK's interests. Rather it allows the rest of the EU to take advantage of the country's fish stocks.

The CFP's quota system, while credited for helping the industry survive (and even reverse the collapse in fish stocks), is now seen as burdensome and preventing further growth.

A recent academic analysis of the current performance of the CFP showed it was not improving the management of the fish stock resources in any of its 17 criteria and was actually making things worse in seven areas.

For eksempel, a 2013 reform of the CFP introduced the landing obligation, the so-called "discard ban", that was designed to stop vessels discarding fish (bycatch) caught alongside the species they were targeting. Environmentalists, and campaigns backed by celebrities such as Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, have long voiced concerns over incidents of bycatch being dumped by fishers operating under the quota system.

This policy is now seen as potentially disastrous by some representatives of Britain's North Sea fishing fleet, as so many different types of fish live in the waters and bycatch is common and often unavoidable. They are concerned that boats would be forced to fill their holds with commercially worthless fish and return to port early. Or by exhausting their quota for some species early in the season, they would be forced to stay in port for the rest of the year, despite having quotas available for other species. Evidence given to the House of Lords suggests that this situation has not arisen as non-compliance and a lack of enforcement has undermined the discard ban.

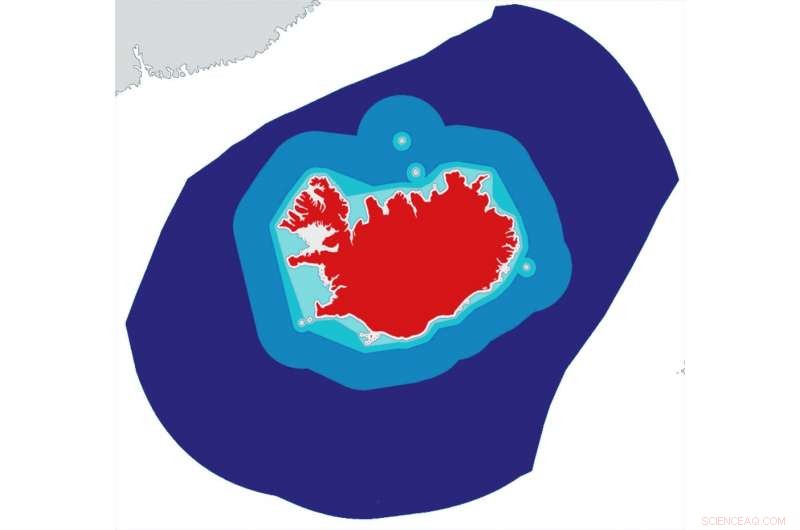

Map of the Icelandic EEZ, and its expansion. Red =Iceland. White =internal waters. Light turquoise =four-mile expansion, 1952. Dark turquoise =12-mile expansion (current extent of territorial waters), 1958. Blue =50-mile expansion, 1972. Dark blue =200-mile expansion (current extent of EEZ), 1975. Credit:Kjallakr/Wikipedia, CC BY-SA

When we interviewed fishers in north-east Scotland in 2018, we found many feared such blanket management across the entire EU would continue to damage their industry because it simply does not take into account the local environment that they work in.

Brexit

The depth of feeling among the UK fishing community was illustrated by the voting figures for the EU referendum in June 2016.

In Banff and Buchan, the constituency in Scotland containing Peterhead and Fraserburgh – the largest and third largest fishing ports in the UK respectively – 54% of people voted to leave the EU, with the size of the fishing industry given as the reason for this result. The result compared to 52% for the whole of the UK and just 38% for Scotland. A survey of members of the UK fishing industry before the vote indicated that 92.8% of correspondents believed that doing so would improve the UK fishing industry by some measure.

But will Brexit really bring the fishing revival so many have promised and hoped for? British politicians have promised a renaissance in UK fishing after leaving the EU. A Fisheries Bill was launched by the environment secretary, Michael Gove, with an aim to "take back control of UK waters". Imidlertid, no definitive plan to remove the UK from the CFP in a transition deal has been made, nor has the industry been given any answers on future access for EU vessels, the apportionment of any new quota – if indeed the quota system remains as it is – the rules that they will be operating under, or even a date on which this will come into effect.

The UK government is seen by many in the fishing industry to be acting against their interests in pursuit of wider goals, for example by using the industry as a bargaining chip in wider UK trade negotiations with the EU.

The fishing industry's distrust of the government has a long tail:many believe they were sacrificed in 1973 by the then prime minister, Edward Heath, in order to secure access to the single market.

A soured relationship

Ironisk, despite the fishing industry's support for Brexit and the popular campaign promises, our research suggests fishers don't simply want to close British waters to European fleets. We interviewed people who were sympathetic to their fellow fishers from abroad and did not wish to see businesses and livelihoods lost. They favour a re-balancing of quotas over time to allow EU vessels to adapt to the change, with all vessels having to adhere to UK rules. This would avoid any situations similar to the Scallop War by ensuring that all vessels with a quota have to abide by local restrictions.

The EU is the main export market for UK fish and fisheries products accounting for 70% of UK fisheries exports by value. Valued at £1.3 billion, this trade far exceeds the £980m value of fish landed in the UK, due to the added value from the processing sector. Some of the remaining 30% of exports that go to countries outside of the EU are governed by trade agreements negotiated by the EU that reduce trade barriers. So the single market, and additional trade agreements, are crucial to the success of the UK fishing industry.

This reliance on trade into the EU puts the industry in a position where unilaterally preventing access to UK waters would likely be met by reciprocal trade barriers and tariffs. This would increase the cost of their product, while reducing access to their biggest market. The question for the government, derefter, is how to balance a political issue against an economic one?

The issue centres on the word "control". If the UK has control of its waters that would simply mean that its government has the power to decide on anything from keeping fishing within UK waters purely for UK vessels, to remaining in or re-entering the CFP, or all points in between. Until the deals are negotiated and signed, the industry will remain in a limbo that has reopened old wounds and reignited distrust in the UK government.

Denne artikel er genudgivet fra The Conversation under en Creative Commons-licens. Læs den originale artikel.

Varme artikler

Varme artikler

-

Statistik afslører nyt, mere præcis indsigt i opadgående mobilitet mellem generationerKredit:CC0 Public Domain Som politisk retorik indeholdende løfter om uddannelse, sociale muligheder og anden udvikling for dårligt stillede mennesker fortsætter med at fylde luftbølgerne, økonomif

Statistik afslører nyt, mere præcis indsigt i opadgående mobilitet mellem generationerKredit:CC0 Public Domain Som politisk retorik indeholdende løfter om uddannelse, sociale muligheder og anden udvikling for dårligt stillede mennesker fortsætter med at fylde luftbølgerne, økonomif -

Forsvundne grave identificeret ved nye arkæologiske metoderUndergrundsbilledteknologi hjælper med at finde tabte grave i Australien. Kredit:Flinders University Arkæologer fra Flinders University bruger banebrydende undergrundsbilledteknologi til at hjælpe

Forsvundne grave identificeret ved nye arkæologiske metoderUndergrundsbilledteknologi hjælper med at finde tabte grave i Australien. Kredit:Flinders University Arkæologer fra Flinders University bruger banebrydende undergrundsbilledteknologi til at hjælpe -

Overhævelse af viden forudsiger anti-etablissements-afstemningLogistiske regressionshældninger og 95 % konfidensintervaller for anti-establishment-afstemninger som funktion af selvopfattet forståelse af traktaten, faktisk kendskab til traktaten, og generel overk

Overhævelse af viden forudsiger anti-etablissements-afstemningLogistiske regressionshældninger og 95 % konfidensintervaller for anti-establishment-afstemninger som funktion af selvopfattet forståelse af traktaten, faktisk kendskab til traktaten, og generel overk -

$2,99 eller $3,00? Vil forskellen på en øre få dig til kassen?Lingjiang Lora Tu, Ph.D., assisterende klinisk professor i marketing ved Baylor Universitys Hankamer School of Business. Kredit:Baylor University En traditionel tro på detailmarkedsføring er, at p

$2,99 eller $3,00? Vil forskellen på en øre få dig til kassen?Lingjiang Lora Tu, Ph.D., assisterende klinisk professor i marketing ved Baylor Universitys Hankamer School of Business. Kredit:Baylor University En traditionel tro på detailmarkedsføring er, at p

- Der er en nem måde at forstå mitose og meiose på

- Får landbrugets nitratproblem til at forsvinde i luften

- NASA observerer ekstrem nedbør over det sydlige Californien

- Et nyt stetoskop slutter sig til kampen mod antallet af børnelungebetændelse

- En liste over trinene i informationsbehandlingscyklussen

- Øget tilgængelighed af vand fra klimaændringer kan frigive flere næringsstoffer til jorden i Ant…