Bekymringer om at sprede jordmikrober bør ikke forsinke søgen efter liv på Mars

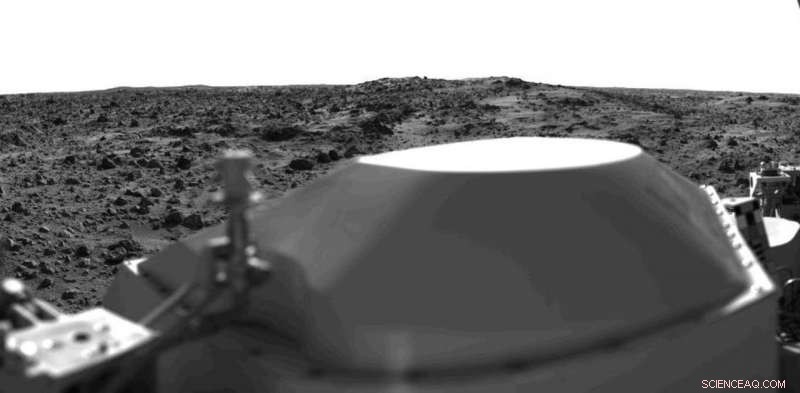

Vikingelanderne i 1970’erne var de sidste, der ledte direkte efter livet på Mars. Kredit:NASA/JPL, CC BY

Der er måske ikke noget større spørgsmål, end om vi er alene i vores solsystem. Da vores rumfartøj finder nye spor om tilstedeværelsen af flydende vand nu eller tidligere på Mars, muligheden for en eller anden form for liv der ser mere sandsynlig ud. På jorden, vand betyder liv, og det er derfor, udforskningen af Mars er styret af ideen om at følge vandet.

Men jagten på liv på Mars er parret med masser af stærke advarsler om, hvordan vi skal sterilisere vores rumfartøj for at undgå at forurene vores naboplanet. Hvordan vil vi vide, hvad der er indfødt Mars, hvis vi utilsigtet sår stedet med jordorganismer? En populær analogi påpeger, at europæere ubevidst bragte kopper til den nye verden, og de tog syfilis med hjem. Tilsvarende det hævdes, vores robotundersøgelser kunne forurene Mars med terrestriske mikroorganismer.

Som en astrobiolog, der forsker i miljøerne på den tidlige Mars, Jeg foreslår, at disse argumenter er vildledende. Den nuværende fare for forurening via ubemandede robotter er faktisk ret lav. Men forurening vil blive uundgåelig, når astronauterne når dertil. NASA, andre agenturer og den private sektor håber at sende menneskelige missioner til Mars i 2030'erne.

Rumorganisationer har længe prioriteret at forhindre forurening frem for vores jagt på liv på Mars. Nu er tiden inde til at revurdere og opdatere denne strategi – før mennesker når dertil og uundgåeligt introducerer Jordens organismer på trods af vores bedste indsats.

Hvad planetariske beskyttelsesprotokoller gør

Argumenter, der kræver ekstra forsigtighed, har gennemsyret Mars -udforskningsstrategier og ført til oprettelse af specifikke vejledende politikker, kendt som planetariske beskyttelsesprotokoller.

Der kræves strenge rengøringsprocedurer på vores rumfartøjer, før de får lov til at prøve områder på Mars, som kan være et levested for mikroorganismer. enten hjemmehørende på Mars eller bragt dertil fra Jorden. Disse områder er mærket af de planetariske beskyttelseskontorer som "Special Regions."

Mikrobiologer indsamler ofte svaberprøver fra gulvet i rene rum under samling af rumfartøjer. Kredit:NASA/JPL-Caltech, CC BY

Bekymringen er, at Ellers, terrestriske angribere kan bringe potentielt liv på Mars i fare. De kunne også forvirre fremtidige forskere, der forsøger at skelne mellem alle indfødte Mars-livsformer og liv, der ankom som forurening fra Jorden via nutidens rumfartøj.

Den sørgelige konsekvens af disse politikker er, at Mars-rumfartøjsprogrammerne på mange milliarder dollar, der drives af rumfartsorganisationer i Vesten, ikke proaktivt har ledt efter liv på planeten siden slutningen af 1970'erne.

Det var da NASAs vikingelandere gjorde det eneste forsøg nogensinde på at finde liv på Mars (eller på en planet uden for Jorden, for den sags skyld). De udførte specifikke biologiske eksperimenter på udkig efter bevis på mikrobielt liv. Siden da, at begyndende biologisk udforskning er skiftet til mindre ambitiøse geologiske undersøgelser, der forsøger kun at demonstrere, at Mars var "beboelig" i fortiden, hvilket betyder, at det havde betingelser, der sandsynligvis kunne understøtte livet.

Værre endnu, hvis et dedikeret livssøgende rumfartøj nogensinde kommer til Mars, Planetariske beskyttelsespolitikker vil tillade den at søge efter liv overalt på Mars-overfladen, undtagen netop de steder, vi har mistanke om, at der kan eksistere liv:Specialregionerne. Bekymringen er, at efterforskning kan forurene dem med terrestriske mikroorganismer.

Kan jordens liv nå det på Mars?

Overvej igen de europæere, der først rejste til den nye verden og tilbage. Ja, kopper og syfilis rejste med dem, mellem menneskelige befolkninger, bor inde i varme kroppe i tempererede breddegrader. Men den situation er irrelevant for Mars-udforskningen. Enhver analogi, der adresserer mulig biologisk udveksling mellem Jorden og Mars, skal tage højde for den absolutte kontrast i planeternes miljøer.

En mere nøjagtig analogi ville være at bringe 12 asiatiske tropiske papegøjer til den venezuelanske regnskov. Om 10 år kan vi med stor sandsynlighed have en invasion af asiatiske papegøjer i Sydamerika. Men hvis vi bringer de samme 12 asiatiske papegøjer til Antarktis, om 10 timer har vi 12 døde papegøjer.

Dr. Carl Sagan poserer med en model af vikingelanderen i Death Valley, Californien. Kredit:NASA, CC BY

Vi ville antage, at ethvert indfødt liv på Mars burde være meget bedre tilpasset til stress fra Mars, end livet på jorden er, og derfor ville udkonkurrere alle mulige landbaserede nytilkomne. Mikroorganismer på Jorden har udviklet sig til at trives i udfordrende miljøer som saltskorper i Atacama-ørkenen eller hydrotermiske åbninger på den dybe havbund. På samme måde, we can imagine any potential Martian biosphere would have experienced enormous evolutionary pressure during billions of years to become expert in inhabiting Mars' today environments. The microorganisms hitchhiking on our spacecraft wouldn't stand much of a chance against super-specialized Martians in their own territory.

So if Earth life cannot survive and, mest vigtigt, reproduce on Mars, concerns going forward about our spacecraft contaminating Mars with terrestrial organisms are unwarranted. This would be the parrots-in-Antarctica scenario.

På den anden side, perhaps Earth microorganisms can, faktisk, survive and create active microbial ecosystems on present-day Mars – the parrots-in-South America scenario. We can then presume that terrestrial microorganisms are already there, carried by any one of the dozens of spacecraft sent from Earth in the last decades, or by the natural exchange of rocks pulled out from one planet by a meteoritic impact and transported to the other.

I dette tilfælde, protection protocols are overly cautious since contamination is already a fact.

Technological reasons the protocols don't make sense

Another argument to soften planetary protection protocols hinges on the fact that current sterilization methods don't actually "sterilize" our spacecraft, a feat engineers still don't know how to accomplish definitively.

The cleaning procedures we use on our robots rely on pretty much the same stresses prevailing on the Martian surface:oxidizing chemicals and radiation. They end up killing only those microorganisms with no chance of surviving on Mars anyway. So current cleaning protocols are essentially conducting an artificial selection experiment, with the result that we carry to Mars only the most hardy microorganisms. This should put into question the whole cleaning procedure.

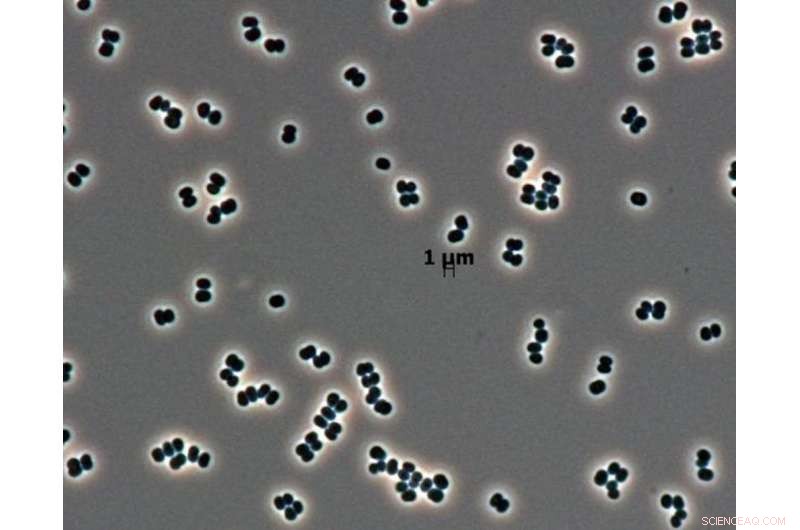

Bacterial species Tersicoccus phoenicis is found in only two places:clean rooms in Florida and South America where spacecraft are assembled for launch. Credit:NASA/JPL-Caltech, CC BY

Further, technology has advanced enough that distinguishing between Earthlings and Martians is no longer a problem. If Martian life is biochemically similar to Earth life, we could sequence genomes of any organisms located. If they don't match anything we know is on Earth, we can surmise it's native to Mars. Then we could add Mars' creatures to the tree of DNA-based life we already know, probably somewhere on its lower branches. And if it is different, we would be able to identify such differences based on its building blocks.

Mars explorers have yet another technique to help differentiate between Earth and Mars life. The microbes we know persist in clean spacecraft assembly rooms provide an excellent control with which to monitor potential contamination. Any microorganism found in a Martian sample identical or highly similar to those present in the clean rooms would very likely indicate contamination – not indigenous life on Mars.

The window is closing

On top of all these reasons, it's pointless to split hairs about current planetary protection guidelines as applied to today's unmanned robots since human explorers are on the horizon. People would inevitably bring microbial hitchhikers with them, because we cannot sterilize humans. Contamination risks between robotic and manned missions are simply not comparable.

Whether the microbes that fly with humans will be able to last on Mars is a separate question – though their survival is probably assured if they stay within a spacesuit or a human habitat engineered to preserve life. But no matter what, they'll definitely be introduced to the Martian environment. Continuing to delay the astrobiological exploration of Mars now because we don't want to contaminate the planet with microorganisms hiding in our spacecrafts isn't logical considering astronauts (and their microbial stowaways) may arrive within two or three decades.

Prior to landing humans on Mars or bringing samples back to Earth, it makes sense to determine whether there is indigenous Martian life. What might robots or astronauts encounter there – and import to Earth? More knowledge now will increase the safety of Earth's biosphere. Trods alt, we still don't know if returning samples could endanger humanity and the terrestrial biosphere. Perhaps reverse contamination should be our big concern.

The main goal of Mars exploration should be to try to find life on Mars and address the question of whether it is a separate genesis or shares a common ancestor with life on Earth. Til sidst, if Mars is lifeless, maybe we are alone in the universe; but if there is or was life on Mars, then there's a zoo out there.

Denne artikel blev oprindeligt publiceret på The Conversation. Læs den originale artikel.

Varme artikler

Varme artikler

-

Buzz Aldrin:Højdesyge tvang evakuering af SydpolenI denne fredag, 2. december kl. 2016, foto leveret af Christina Korp, ret, Buzz Aldrin ligger i en hospitals seng i Christchurch, New Zealand. Aldrin, den anden mand, der gik på månen, blev evakueret

Buzz Aldrin:Højdesyge tvang evakuering af SydpolenI denne fredag, 2. december kl. 2016, foto leveret af Christina Korp, ret, Buzz Aldrin ligger i en hospitals seng i Christchurch, New Zealand. Aldrin, den anden mand, der gik på månen, blev evakueret -

Tester Tjernobyl-svampe som et strålingsskjold for astronauterKredit:Pixabay/CC0 Public Domain Et team af forskere fra University of North Carolina ved Charlotte og Stanford University har testet levedygtigheden af at bruge en type svamp, der vokser i nogl

Tester Tjernobyl-svampe som et strålingsskjold for astronauterKredit:Pixabay/CC0 Public Domain Et team af forskere fra University of North Carolina ved Charlotte og Stanford University har testet levedygtigheden af at bruge en type svamp, der vokser i nogl -

Hubble løser kosmisk whodunit med interstellar retsmedicinDette er en fotomosaik af et kantbillede af Mælkevejen, kigger mod den centrale bule. Overlejret på det er radioteleskopbilleder, farvet pink, af de strakte, bueformet magellansk strøm under galaksepl

Hubble løser kosmisk whodunit med interstellar retsmedicinDette er en fotomosaik af et kantbillede af Mælkevejen, kigger mod den centrale bule. Overlejret på det er radioteleskopbilleder, farvet pink, af de strakte, bueformet magellansk strøm under galaksepl -

Omvej via gravitationslinse gør en fjern galakse synligMAGIC-teleskoperne på den kanariske ø La Palma vises. Kredit:Robert Wagner Aldrig før har astrofysikere målt lys med så høj energi fra et himmelobjekt så langt væk. For omkring 7 milliarder år sid

Omvej via gravitationslinse gør en fjern galakse synligMAGIC-teleskoperne på den kanariske ø La Palma vises. Kredit:Robert Wagner Aldrig før har astrofysikere målt lys med så høj energi fra et himmelobjekt så langt væk. For omkring 7 milliarder år sid

- Leder vi efter lykken alle de forkerte steder?

- Alexa, send morgenmad:Amazon lancerer Echo til hoteller

- Hexameriske lanthanid-organiske kapsler med tertiær struktur, nye funktioner

- Forskere sporer mønstre for øvækst i krystaller

- 1N4007 Diodespecifikationer

- Er dit hjem i fare for at opleve en naturkatastrofe?