Moderne alkymister gør kemien grønnere

Gamle alkymister forsøgte at gøre bly og andre almindelige metaller til guld og platin. Moderne kemikere i Paul Chiriks laboratorium i Princeton omdanner reaktioner, der har været afhængige af miljøvenlige ædle metaller, finde billigere og grønnere alternativer til udskiftning af platin, rhodium og andre ædle metaller i lægemiddelproduktion og andre reaktioner.

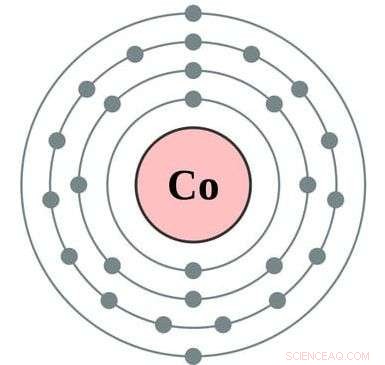

De har fundet en revolutionerende tilgang, der bruger kobolt og methanol til at producere et epilepsimedicin, der tidligere krævede rhodium og dichlormethan, et giftigt opløsningsmiddel. Deres nye reaktion virker hurtigere og billigere, og det har sandsynligvis en meget mindre miljøpåvirkning, sagde Chirik, Edwards S. Sanford professor i kemi. "Dette fremhæver et vigtigt princip inden for grøn kemi - at den mere miljømæssige løsning også kan være den foretrukne kemisk, "sagde han. Undersøgelsen blev offentliggjort i tidsskriftet Videnskab den 25. maj.

"Farmaceutisk opdagelse og proces involverer alle slags eksotiske elementer, "Sagde Chirik." Vi startede dette program for måske 10 år siden, og det var virkelig motiveret af omkostninger. Metaller som rhodium og platin er virkelig dyre, men efterhånden som arbejdet har udviklet sig, vi indså, at der er meget mere i det end blot at prissætte. ... der er enorme miljøhensyn, hvis du tænker på at grave platin op af jorden. Typisk, du skal gå en kilometer dyb og flytte 10 tons jord. Det har et massivt kuldioxidaftryk. "

Chirik og hans forskerhold indgik et samarbejde med kemikere fra Merck &Co., Inc., at finde mere miljøvenlige måder at skabe de materialer, der er nødvendige for moderne lægemiddelkemi. Samarbejdet er blevet muliggjort af National Science Foundation's Grant Opportunities for Academic Liaison with Industry (GOALI) program.

Et vanskeligt aspekt er, at mange molekyler har højre- og venstrehåndede former, der reagerer forskelligt, med nogle gange farlige konsekvenser. Food and Drug Administration har strenge krav til at sikre, at medicin kun har en "hånd" ad gangen, kendt som single-enantiomer-lægemidler.

"Kemikere udfordres til at opdage metoder til kun at syntetisere en hånd af lægemiddelmolekyler frem for at syntetisere begge og derefter adskille, "sagde Chirik." Metalkatalysatorer, historisk baseret på ædle metaller som rhodium, har fået til opgave at løse denne udfordring. Vores papir viser, at et mere jordfyldt metal, kobolt, kan bruges til at syntetisere epilepsimedicinen Keppra som kun en hånd. "

Fem år siden, forskere i Chiriks laboratorium viste, at kobolt kunne lave enkelt-enantiomer organiske molekyler, men kun ved hjælp af relativt enkle og ikke medicinsk aktive forbindelser - og brug af giftige opløsningsmidler.

"Vi blev inspireret til at skubbe vores demonstration af princippet ind i virkelige eksempler og demonstrere, at kobolt kunne overgå ædle metaller og arbejde under mere miljøkompatible forhold, "sagde han. De fandt ud af, at deres nye koboltbaserede teknik er hurtigere og mere selektiv end den patenterede rhodium-tilgang.

"Vores papir demonstrerer et sjældent tilfælde, hvor et jord-rigeligt overgangsmetal kan overgå et ædle metals ydeevne ved syntesen af enkelt-enantiomerlægemidler, "sagde han." Det, vi begynder at overgå til, er, at de jord-rigelige katalysatorer ikke kun erstatter ædle metaller, men de giver tydelige fordele, om det er ny kemi, som ingen nogensinde har set før, eller det er forbedret reaktivitet eller reduceret miljøaftryk. "

Basismetaller er ikke kun billigere og meget miljøvenligere end sjældne metaller, men den nye teknik fungerer i methanol, which is much greener than the chlorinated solvents that rhodium requires.

"The manufacture of drug molecules, because of their complexity, is one of the most wasteful processes in the chemical industry, " said Chirik. "The majority of the waste generated is from the solvent used to conduct the reaction. The patented route to the drug relies on dichloromethane, one of the least environmentally friendly organic solvents. Our work demonstrates that Earth-abundant catalysts not only operate in methanol, a green solvent, but also perform optimally in this medium.

"This is a transformative breakthrough for Earth-abundant metal catalysts, as these historically have not been as robust as precious metals. Our work demonstrates that both the metal and the solvent medium can be more environmentally compatible."

Methanol is a common solvent for one-handed chemistry using precious metals, but this is the first time it has been shown to be useful in a cobalt system, noted Max Friedfeld, the first author on the paper and a former graduate student in Chirik's lab.

Cobalt's affinity for green solvents came as a surprise, said Chirik. "For a decade, catalysts based on Earth-abundant metals like iron and cobalt required very dry and pure conditions, meaning the catalysts themselves were very fragile. By operating in methanol, not only is the environmental profile of the reaction improved, but the catalysts are much easier to use and handle. This means that cobalt should be able to compete or even outperform precious metals in many applications that extend beyond hydrogenation."

The collaboration with Merck was key to making these discoveries, noted the researchers.

Chirik said:"This is a great example of an academic-industrial collaboration and highlights how the very fundamental—how do electrons flow differently in cobalt versus rhodium?—can inform the applied—how to make an important medicine in a more sustainable way. I think it is safe to say that we would not have discovered this breakthrough had the two groups at Merck and Princeton acted on their own."

The key was volume, said Michael Shevlin, an associate principal scientist at the Catalysis Laboratory in the Department of Process Research &Development at Merck &Co., Inc., and a co-author on the paper.

"Instead of trying just a few experiments to test a hypothesis, we can quickly set up large arrays of experiments that cover orders of magnitude more chemical space, " Shevlin said. "The synergy is tremendous; scientists like Max Friedfeld and [co-author and graduate student] Aaron Zhong can conduct hundreds of experiments in our lab, and then take the most interesting results back to Princeton to study in detail. What they learn there then informs the next round of experimentation here."

Chirik's lab focuses on "homogenous catalysis, " the term for reactions using materials that have been dissolved in industrial solvents.

"Homogenous catalysis is usually the realm of these precious metals, the ones at the bottom of the periodic table, " Chirik said. "Because of their position on the periodic table, they tend to go by very predictable electron changes—two at a time—and that's why you can make jewelry out of these elements, because they don't oxidize, they don't interact with oxygen. So when you go to the Earth-abundant elements, usually the ones on the first row of the periodic table, the electronic structure—how the electrons move in the element—changes, and so you start getting one-electron chemistry, and that's why you see things like rust for these elements.

Chirik's approach proposes a radical shift for the whole field, said Vy Dong, a chemistry professor at the University of California-Irvine who was not involved in the research. "Traditional chemistry happens through what they call two-electron oxidations, and Paul's happens through one-electron oxidation, " she said. "That doesn't sound like a big difference, but that's a dramatic difference for a chemist. That's what we care about—how things work at the level of electrons and atoms. When you're talking about a pathway that happens via half of the electrons that you'd normally expect, it's a big deal. ... That's why this work is really exciting. You can imagine, once we break free from that mold, you can start to apply it to other things, også."

"We're working in an area of the periodic table where people haven't, for a long time, so there's a huge wealth of new fundamental chemistry, " said Chirik. "By learning how to control this electron flow, the world is open to us."

Sidste artikelSådan ser et stretchy kredsløb ud

Næste artikelProteiner som shuttle service til målrettet administration af medicin

Varme artikler

Varme artikler

-

Følsom ny test påviser antistoffer mod SARS-CoV-2 på kun 10 minutterEn ny lateral flow immunoassay kan påvise antistoffer mod SARS-CoV-2, som vises som en lys orange streg, når de placeres på en fluorescenslæser (højre). Kredit:Guanfeng Lin Da COVID-19-kurven vise

Følsom ny test påviser antistoffer mod SARS-CoV-2 på kun 10 minutterEn ny lateral flow immunoassay kan påvise antistoffer mod SARS-CoV-2, som vises som en lys orange streg, når de placeres på en fluorescenslæser (højre). Kredit:Guanfeng Lin Da COVID-19-kurven vise -

Anvendelse af syrer og baserSyrer og baser sidder i modsatte ender af pH eller potentiale for brint, skala: Syrer sidder tættere på nul, og baser sidder tættere på 14. Hvert kemikalie har et andet pH-niveau og sammen med det, en

Anvendelse af syrer og baserSyrer og baser sidder i modsatte ender af pH eller potentiale for brint, skala: Syrer sidder tættere på nul, og baser sidder tættere på 14. Hvert kemikalie har et andet pH-niveau og sammen med det, en -

Video:Hvordan sølv nanopartikler skærer lugtKredit:The American Chemical Society Trendy træningstøj kan reklamere for, at specielle sølv nanopartikler indlejret i stoffet vil skære den svedige lugt, der opbygges fra gentagne fitnessbesøg. D

Video:Hvordan sølv nanopartikler skærer lugtKredit:The American Chemical Society Trendy træningstøj kan reklamere for, at specielle sølv nanopartikler indlejret i stoffet vil skære den svedige lugt, der opbygges fra gentagne fitnessbesøg. D -

Ny tilgang kan hjælpe myndighederne med at reagere hurtigere på luftbårne radiologiske truslerKredit:North Carolina State University Forskere fra North Carolina State University har udviklet en ny teknik, der bruger eksisterende teknologier til at detektere potentielle luftbårne radiologis

Ny tilgang kan hjælpe myndighederne med at reagere hurtigere på luftbårne radiologiske truslerKredit:North Carolina State University Forskere fra North Carolina State University har udviklet en ny teknik, der bruger eksisterende teknologier til at detektere potentielle luftbårne radiologis

- Opdagelse af nye hajarter højdepunkter behov for at beskytte Belize farvande

- Undersøgelse rapporterer højharmonisk generering i et epsilon-nær-nul materiale

- Klimaændringer ændrer tidspunktet for europæiske oversvømmelser

- NASA observerer kraftig monsunregn i Sri Lanka

- Letvægts elektriske armbåndsvarmere til konstant, bærbar varme

- Frit fald (fysik): Definition, formel, problemer og løsninger (med eksempler)