I dag føles hedebølger meget varmere end varmeindekset antyder

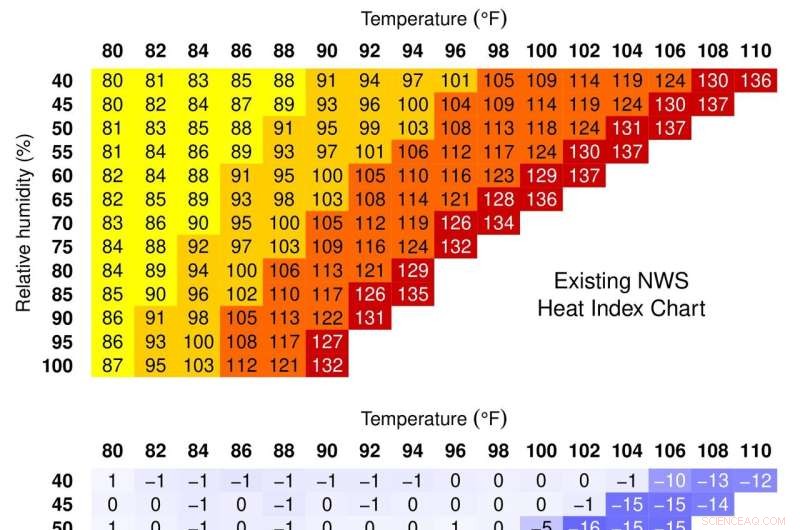

Den længe brugte varmeindekstabel (øverst) undervurderer den tilsyneladende temperatur for de mest ekstreme varme- og fugtforhold, der forekommer i dag (i midten). Den korrigerede version (nederst) er nøjagtig over hele området af temperaturer og fugtigheder, som mennesker vil støde på i forbindelse med klimaændringer. Kredit:David Romps og Yi-Chuan Lu, UC Berkeley

Hvis du har kigget på varmeindekset under sommerens klæbrige hedebølger og tænkt:"Det føles helt sikkert varmere", har du måske ret.

En analyse foretaget af klimaforskere ved University of California, Berkeley, finder, at den tilsyneladende temperatur eller varmeindeks, beregnet af meteorologer og National Weather Service (NWS) for at indikere, hvor varmt det føles - under hensyntagen til fugtigheden - undervurderer den opfattede temperatur i de mest svulmende dage, vi nu oplever, nogle gange med mere end 20 grader Fahrenheit.

Fundet har betydning for dem, der lider under disse hedebølger, da varmeindekset er et mål for, hvordan kroppen håndterer varme, når luftfugtigheden er høj, og sveden bliver mindre effektiv til at køle os ned. Sveden og rødmen – hvor blod ledes til kapillærer tæt på huden for at sprede varmen – og tøjet er de vigtigste måder, hvorpå mennesker tilpasser sig varme temperaturer.

Et højere varmeindeks betyder, at den menneskelige krop er mere stresset under disse hedebølger, end offentlige sundhedsmyndigheder måske er klar over, siger forskerne. NWS anser i øjeblikket et varmeindeks over 103 for at være farligt og over 125 for at være ekstremt farligt.

"Det meste af tiden er varmeindekset, som National Weather Service giver dig, den helt rigtige værdi. Det er kun i disse ekstreme tilfælde, hvor de får det forkerte tal," sagde David Romps, UC Berkeley professor i jord og planeter. videnskab. "Hvor det betyder noget er, når du begynder at kortlægge varmeindekset tilbage til fysiologiske tilstande, og du indser, åh, disse mennesker bliver stressede til en tilstand med meget forhøjet blodgennemstrømning i huden, hvor kroppen er tæt på at løbe tør for tricks til at kompensere for denne form for varme og fugtighed. Så vi er tættere på den kant, end vi troede, vi var før."

Romps og kandidatstuderende Yi-Chuan Lu detaljerede deres analyse i et papir, der er accepteret af tidsskriftet Environmental Research Letters og lagt online 12. august.

Varmeindekset blev udtænkt i 1979 af en tekstilfysiker, Robert Steadman, som skabte simple ligninger til at beregne, hvad han kaldte den relative "sultriness" af varme og fugtige såvel som varme og tørre forhold i løbet af sommeren. Han så det som et supplement til den vindafkølingsfaktor, der almindeligvis bruges om vinteren til at vurdere, hvor koldt det føles.

Hans model tog højde for, hvordan mennesker regulerer deres indre temperatur for at opnå termisk komfort under forskellige ydre betingelser for temperatur og fugtighed – ved bevidst at ændre tykkelsen af tøjet eller ubevidst justere respiration, sved og blodgennemstrømning fra kroppens kerne til huden.

In his model, the apparent temperature under ideal conditions—an average-sized person in the shade with unlimited water—is how hot someone would feel if the relative humidity were at a comfortable level, which Steadman took to be a vapor pressure of 1,600 pascals.

For example, at 70% relative humidity and 68 F—which is often taken as average humidity and temperature—a person would feel like it's 68 F. But at the same humidity and 86 F, it would feel like 94 F.

The heat index has since been adopted widely in the United States, including by the NWS, as a useful indicator of people's comfort. But Steadman left the index undefined for many conditions that are now becoming increasingly common. For example, for a relative humidity of 80%, the heat index is not defined for temperatures above 88 F or below 59 F. Today, temperatures routinely rise above 90 F for weeks at a time in some areas, including the Midwest and Southeast.

To account for these gaps in Steadman's chart, meteorologists extrapolated into these areas to get numbers, Romps said, that are correct most of the time, but not based on any understanding of human physiology.

"There's no scientific basis for these numbers," Romps said.

He and Lu set out to extend Steadman's work so that the heat index is accurate at all temperatures and all humidities between zero and 100%.

"The original table had a very short range of temperature and humidity and then a blank region where Steadman said the human model failed," Lu said. "Steadman had the right physics. Our aim was to extend it to all temperatures so that we have a more accurate formula."

One condition under which Steadman's model breaks down is when people perspire so much that sweat pools on the skin. At that point, his model incorrectly had the relative humidity at the skin surface exceeding 100%, which is physically impossible.

"It was at that point where this model seems to break, but it's just the model telling him, hey, let sweat drip off the skin. That's all it was," Romps said. "Just let the sweat drop off the skin."

That and a few other tweaks to Steadman's equations yielded an extended heat index that agrees with the old heat index 99.99% of the time, Romps said, but also accurately represents the apparent temperature for regimes outside those Steadman originally calculated. When he originally published his apparent temperature scale, he considered these regimes too rare to worry about, but high temperatures and humidities are becoming increasingly common because of climate change.

Romps and Lu had published the revised heat index equation earlier this year. In the most recent paper, they apply the extended heat index to the top 100 heat waves that occurred between 1984 and 2020. The researchers find mostly minor disagreements with what the NWS reported at the time, but also some extreme situations where the NWS heat index was way off.

One surprise was that seven of the 10 most physiologically stressful heat waves over that time period were in the Midwest—mostly in Illinois, Iowa and Missouri—not the Southeast, as meteorologists assumed. The largest discrepancies between the NWS heat index and the extended heat index were seen in a wide swath, from the Great Lakes south to Louisiana.

During the July 1995 heat wave in Chicago, for example, which killed at least 465 people, the maximum heat index reported by the NWS was 135 F, when it actually felt like 154 F. The revised heat index at Midway Airport, 141 F, implies that people in the shade would have experienced blood flow to the skin that was 170% above normal. The heat index reported at the time, 124 F, implied only a 90% increase in skin blood flow. At some places during the heat wave, the extended heat index implies that people would have experienced an increase of 820% above normal skin blood flow.

"I'm no physiologist, but a lot of things happen to the body when it gets really hot," Romps said. "Diverting blood to the skin stresses the system because you're pulling blood that would otherwise be sent to internal organs and sending it to the skin to try to bring up the skin's temperature. The approximate calculation used by the NWS, and widely adopted, inadvertently downplays the health risks of severe heat waves."

Physiologically, the body starts going haywire when the skin temperature rises to equal the body's core temperature, typically taken as 98.6 F. After that, the core temperature begins to increase. The maximum sustainable core temperature is thought to be 107 F—the threshold for heat death. For the healthiest of individuals, that threshold is reached at a heat index of 200 F.

Luckily, humidity tends to decrease as temperature increases, so Earth is unlikely to reach those conditions in the next few decades. Less extreme—though still deadly—conditions are nevertheless becoming common around the globe.

"A 200 F heat index is an upper bound of what is survivable," Romps said. "But now that we've got this model of human thermoregulation that works out at these conditions, what does it actually mean for the future habitability of the United States and the planet as a whole? There are some frightening things we are looking at." + Udforsk yderligere

Hot and getting hotter:Five essential reads on high temps and human bodies

Varme artikler

Varme artikler

-

Røg, ekstrem varme udgør en hård test for vinmarker på vestkystenAlejandra Morales Buscio, af Salem, Oregon, rækker op for at trække bladets baldakin over pinot noir druer på torsdag, 8. juli, 2021, at skygge frugten fra solen, på Willamette Valley Vineyards i Turn

Røg, ekstrem varme udgør en hård test for vinmarker på vestkystenAlejandra Morales Buscio, af Salem, Oregon, rækker op for at trække bladets baldakin over pinot noir druer på torsdag, 8. juli, 2021, at skygge frugten fra solen, på Willamette Valley Vineyards i Turn -

Finansielle omkostninger forbundet med landmænd risikerer at tageKredit:University of Aberdeen Landmænd risikerer personlig sikkerhed på grund af økonomisk pres ifølge ny forskning fra University of Aberdeen. Forskningen, offentliggjort i Journal of Agromedici

Finansielle omkostninger forbundet med landmænd risikerer at tageKredit:University of Aberdeen Landmænd risikerer personlig sikkerhed på grund af økonomisk pres ifølge ny forskning fra University of Aberdeen. Forskningen, offentliggjort i Journal of Agromedici -

Orkanen Dorian:Hvor den ramte, hvor det er på vej hen, og hvorfor det er så ødelæggendeOrkanen Dorians sti fra dens fødsel sydøst for De Små Antiller til tirsdag den 3. september, 2019. Kredit:NOAA Mindst syv mennesker er døde i kølvandet på orkanen Dorian på Bahamas, selvom dette t

Orkanen Dorian:Hvor den ramte, hvor det er på vej hen, og hvorfor det er så ødelæggendeOrkanen Dorians sti fra dens fødsel sydøst for De Små Antiller til tirsdag den 3. september, 2019. Kredit:NOAA Mindst syv mennesker er døde i kølvandet på orkanen Dorian på Bahamas, selvom dette t -

Ny teknik registrerer små partikler af plast i sne, regn og endda jordKredit:Pixabay/CC0 Public Domain Sneen smelter måske, men det efterlader forurening bag sig i form af mikro- og nanoplast ifølge en McGill-undersøgelse, der for nylig blev offentliggjort i Miljøf

Ny teknik registrerer små partikler af plast i sne, regn og endda jordKredit:Pixabay/CC0 Public Domain Sneen smelter måske, men det efterlader forurening bag sig i form af mikro- og nanoplast ifølge en McGill-undersøgelse, der for nylig blev offentliggjort i Miljøf

- Hybrid energihøster genererer elektricitet fra vibrationer og sollys

- Reaktion på ekstremistiske angreb:For muslimske ledere, Det er forbandet, hvis du gør det forbande…

- Gravitationsbølger! Eller de kvidre, der beviser, at Einstein havde ret

- Forskere opnår næsten øjeblikkelig magnetisering af stof med lys

- Ny forskning finder dyb evolutionær oprindelse af et unikt pattedyrs anatomiske mønster

- Bor kan danne en ren honningkage, grafen-lignende 2-D struktur