EPA-handling øger græsrodsdriften for at reducere for evigt giftige kemikalier

Kredit:Pixabay/CC0 Public Domain

Indsugningspumperne, der engang trak 6 millioner gallons vand om dagen fra Oostanaula-floden, sidder nu for det meste i dvale i denne by i det nordvestlige Georgia.

Lokale embedsmænd hævder, at flere år med forurening miles opstrøms sendte giftige perfluoralkyl- og polyfluoralkylstoffer, kendt som PFAS, ind i Roms vandforsyning, hvilket gjorde det potentielt farligt for byens omkring 37.000 indbyggere. En vandkildeomskifter fra Oostanaula og ekstra behandling har reduceret sporene af kemikalierne, der løber gennem beboernes vandhaner, men de har ikke elimineret PFAS fra samfundets vandforsyning.

Testresultater, der fandt forurening i Rom, har givet genlyd i samfund over hele landet, mens forskere og regulatorer kæmper med bekymringer over konsekvenserne af at indtage de allestedsnærværende kemikalier. Nu accelererer Miljøstyrelsen debatten. I juni udsendte EPA nye meddelelser om PFAS i drikkevand, der sænker det niveau, som regulatorer anser for sikkert for fire kemikalier i familien, herunder to af de mest almindelige, PFOA og PFOS.

EPA's sundhedsrådgivning kan ikke håndhæves juridisk. Men agenturet forventes i år at foreslå nye grænser for PFAS i offentlige vandsystemer. Hvis disse drikkevandsbestemmelser afspejler EPA's seneste råd, bliver vandsystemoperatører på landsplan nødt til at handle for at imødegå tilstedeværelsen af disse kemikalier.

"Det er et ganske vigtigt budskab," sagde Dr. Philippe Grandjean, en PFAS-ekspert og en adjungeret miljøsundhedsprofessor ved Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. "Det her er overalt.''

Environmental Working Group, en forsknings- og fortalervirksomhed, der sporer PFAS, sagde, at den har registreret mere end 2.800 steder i USA, der har PFAS-kontamination. Offentlige optegnelser viser, at kemikalierne er dukket op i vandprøver indsamlet fra hjemmets vandbrønde, kirker, skoler, militærbaser, plejehjem og kommunale vandforsyninger i små byer som Rom og storbyer som Chicago.

De er også til stede i næsten alle amerikaneres blod, ifølge undersøgelser. Og nogle PFAS-forbindelser bioakkumuleres - hvilket betyder, at kemiske koncentrationer ikke let fjernes i kroppen og i stedet stiger over tid, efterhånden som folk indtager spormængder hver dag.

I juli sagde en rapport fra National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, at PFAS-test bør tilbydes til folk, der sandsynligvis har været udsat for høje niveauer gennem deres job, eller dem, der bor i områder med kendt PFAS-forurening. Grandjean, who helped review the report for the National Academies, said the committee concluded that "people have a right to know their exposure level and to be offered proper health care follow-up." He said that doing so is "very important and, in my mind, necessary."

Both the EPA advisories and the National Academies' report follow steady grassroots efforts to curb PFAS chemicals, which have been used in consumer products for decades. Since their invention in the 1940s, the compounds—known by the moniker "forever chemicals" because they don't break down quickly—have been widely applied to household and industrial products, including carpet, waterproof clothes, and nonstick cookware.

PFAS' presence in firefighting foam, food packaging, and even dental floss poses an ongoing challenge. And efforts to reduce PFAS resemble the often-frustrating, decades-long campaign to eliminate another environmental hazard—lead—from homes, soil, and water.

"There has been a dramatic increase in advocacy and public awareness about PFAS," said Alissa Cordner, an expert on the chemicals and an environmental sociology professor at Whitman College in Walla Walla, Washington.

In their report, researchers for the National Academies said they found links between exposure to PFAS and four health conditions:decreased immune response, elevated cholesterol, decreased infant and fetal growth, and increased risk of kidney cancer. The report also found a possible association between the chemicals and breast cancer, changes in liver enzymes, increased risk of testicular cancer, and thyroid disease.

And EPA officials said the agency's latest advisories are based on new science and account for indications "that some negative health effects may occur with concentrations of PFOA or PFOS in water that are near zero."

Most states don't regulate PFAS, though.

That makes the EPA advisories important, said Jamie DeWitt, a professor of pharmacology and toxicology at East Carolina University. "The message from the EPA is that if these PFAS can be detected in drinking water, they pose health risks," she said.

The American Chemistry Council, an industry trade group, pushed back against the advisories and recently asked a federal court to vacate them, saying that the agency process was "scientifically flawed and procedurally improper" and set "impossibly low standards for PFOA and PFOS in drinking water." In a June statement, the council said PFAS have important uses, including in renewable energy efforts and medical supplies.

One producer of PFAS, 3M, said in a statement that the company "acted responsibly in connection with products containing PFAS and will vigorously defend its record of environmental stewardship."

The compounds' development took off with initial hits in Teflon and later Scotchgard. There are 12,000 variations of them now, but only about 150 are being studied by scientists and government agencies, DeWitt said.

U.S. manufacturers voluntarily phased out PFOS and PFOA, the two most extensively produced, but they're still found in drinking water. The city of Rome is among 10 North Georgia communities where PFOS or PFOA have been found in drinking water supplies at higher levels than the EPA advisories declare is safe, the state's environmental regulatory agency said.

Six years ago, officials in Rome were forced to switch the city's water supply from the Oostanaula to the nearby Etowah River, a brownish tributary that merges with the Oostanaula near a downtown bridge. Years of chemical contamination in the Oostanaula that Rome officials said begins dozens of miles upstream in Dalton made the water potentially dangerous. They said that in Dalton, the epicenter of U.S. carpet manufacturing, industrial waste containing PFAS has leached into the Conasauga River, which flows into the Oostanaula.

Officials in Rome plan to build a $100 million reverse-osmosis filtering system to remove the chemicals from the city's water supply. Ratepayers will foot the bill, although a lawsuit filed by the city against carpet manufacturers and their chemical suppliers aims to recover those costs. A separate lawsuit filed by a Rome resident and ratepayer levies similar accusations against the upstream companies. Defendants in the two Rome-based suits have denied the allegations.

The EPA announced $1 billion in grant funding so states can address PFAS and other contaminants in drinking water. But modifications to public water systems nationwide will likely outstrip that allocation quickly.

Downstream from Rome, officials in the Alabama cities of Centre and Gadsden have reported high levels of PFAS in the Coosa River and filed lawsuits against carpet makers. The Gadsden lawsuit is expected to go to trial in October.

The chemicals have drawn a flurry of litigation over the past two decades. A Bloomberg Law analysis found more than 6,400 PFAS-related lawsuits filed in federal courts between July 2005 and March 2022.

Substantial payouts have followed. DuPont and Chemours, which made PFAS products for decades, settled more than 3,500 lawsuits in 2017 for more than $670 million. Both companies denied wrongdoing. And 3M settled a lawsuit from the state of Minnesota for $850 million. The same company settled litigation in the Decatur, Alabama, area for $98 million.

The EPA now should cast a broader net to consider the wide variety of the chemicals, Cordner said. "The persistence of PFAS means we'll be dealing with this for a long time," she said. "Because of their sheer quantity, we need to treat PFAS as a class. We can't go chemical by chemical."

EPA spokesperson Tim Carroll said in an email to KHN that the agency is working to divide the large class of PFAS into smaller categories based on similarities such as chemical structure, physical and chemical properties, and toxicological properties. That work, he said, would "accelerate the effectiveness of regulations, enforcement actions, and the tools and technologies needed to remove PFAS from air, land, and water."

In the meantime, some companies and the military have moved to stop using the chemicals.

The Green Science Policy Institute, an environmental advocacy group, has developed a list of PFAS-free products, including rain gear and apparel, shoes, baby products, cosmetics, and dental floss.

Two years ago, Home Depot and Lowe's said they wouldn't sell carpets or rugs with PFAS in them. This year, the textile manufacturer Milliken said it would eliminate all PFAS from its facilities by the end of 2022.

A handful of flooring companies have followed suit. Dalton-based Shaw Industries, a defendant in the Rome lawsuits, said it has stopped using PFAS in soil and stain treatments for residential and commercial carpet products.

The Coosa River Basin Initiative, a Rome-based environmental advocacy organization, has been tracking the PFAS issue closely. Its executive director, Jesse Demonbreun-Chapman, said the EPA has moved "at lightning speed'' on PFAS, compared with other agency actions.

But unless the eventual regulations are sweeping and the cleanups extensive, he said, "we the people will be guinea pigs for PFAS-related health problems." + Udforsk yderligere

It's raining PFAS:Even in Antarctica and on the Tibetan Plateau, rainwater is unsafe to drink

2022 Kaiser Health News.

Distribueret af Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Varme artikler

Varme artikler

-

Verdens største bølger:Hvordan klimaforandringer kan udløse store jordskred og mega-tsunamierI oktober 2015, et massivt jordskred faldt i Taan Fiord og skabte en tsunami, der fjernede landet mere end 10 kilometer fra rutsjebanen. Kredit:Ground Truth Trekking, CC BY-NC For godt 60 år siden

Verdens største bølger:Hvordan klimaforandringer kan udløse store jordskred og mega-tsunamierI oktober 2015, et massivt jordskred faldt i Taan Fiord og skabte en tsunami, der fjernede landet mere end 10 kilometer fra rutsjebanen. Kredit:Ground Truth Trekking, CC BY-NC For godt 60 år siden -

Sri Lankas embedsmænd forbereder sig på olieudslip fra synkende skibMV X-Press Pearl var på vej til Sri Lanka med hundredvis af tons kemikalier og plastik om bord, da den brød i brand. Sri Lankas myndigheder sagde torsdag, at de forbereder sig på det værst tænkeli

Sri Lankas embedsmænd forbereder sig på olieudslip fra synkende skibMV X-Press Pearl var på vej til Sri Lanka med hundredvis af tons kemikalier og plastik om bord, da den brød i brand. Sri Lankas myndigheder sagde torsdag, at de forbereder sig på det værst tænkeli -

USA's østkyst holder varsomt øje med Irma, endnu en kraftig orkanDette billede opnået fra National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration viser orkanen Irma (R) den 3. september, 2017 Knap en uge efter orkanen Harvey ødelagde store dele af den amerikanske golfk

USA's østkyst holder varsomt øje med Irma, endnu en kraftig orkanDette billede opnået fra National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration viser orkanen Irma (R) den 3. september, 2017 Knap en uge efter orkanen Harvey ødelagde store dele af den amerikanske golfk -

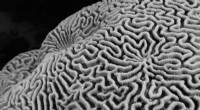

Robuste koraller grundet for at modstå koralblegningNy forskning har fundet robuste koraller, herunder denne hjernekoral (Leptoria), kan være mere modstandsdygtig, i det mindste på kort sigt, til blegning. Kredit:ARC CoE for Coral Reef Studies/ Christo

Robuste koraller grundet for at modstå koralblegningNy forskning har fundet robuste koraller, herunder denne hjernekoral (Leptoria), kan være mere modstandsdygtig, i det mindste på kort sigt, til blegning. Kredit:ARC CoE for Coral Reef Studies/ Christo

- Træ du kan lide en drink? Japans hold opfinder træsprit

- Hvilken enhed opfandt Douglas Engelbart?

- At finde en nøgle til at låse op for blokeret differentiering i mikroRNA-mangelfulde embryonale st…

- Grafen organisk solcelle, eller, vil jogger-t-shirts en dag drive deres mobiltelefoner?

- En bæredygtighedsindikator til at sammenligne cykelvenligheden i amerikanske byer

- Hvilke elementer udgør bagningssoda?