DNA bruges ofte til at opklare forbrydelser. Men hvordan fungerer DNA-profilering egentlig?

Kredit:thinkhubstudio/Shutterstock

DNA-profilering er ofte i nyhederne. Offentlig interesse vækkes, når DNA bruges til at identificere en mistænkt eller menneskelige efterladenskaber, eller løser en kold sag, der synes næsten glemt.

Meget indimellem er det i medierne, når processen ikke fungerer, som den skal.

Så hvad er DNA-profilering, og hvordan fungerer det – og hvorfor virker det nogle gange ikke?

En kort historie om DNA-profilering

DNA-profilering, som det har været kendt siden 1994, har været brugt i det strafferetlige system siden slutningen af 1980'erne og blev oprindeligt kaldt "DNA-fingeraftryk."

DNA'et i hvert menneske er meget ens - faktisk op til 99,9% identisk. Men mærkeligt nok er omkring 98 % af DNA'et i vores celler ikke genrelateret (dvs. har ingen kendt funktion).

Dette ikke-kodende DNA består stort set af sekvenser af de fire baser, der udgør DNA'et i hver celle.

Men af ukendte årsager gentages nogle sektioner af sekvensen:et eksempel er TCTATCTATCTATCTATCTA, hvor sekvensen TCTA gentages fem gange. Mens antallet af gange denne DNA-sekvens gentages er konstant i en person, kan det variere mellem mennesker. En person kan have 5 gentagelser, men en anden 6, eller 7 eller 8.

Der er et stort antal varianter og alle mennesker falder ind i en af dem. Påvisningen af disse gentagelser er grundlaget for moderne DNA-profilering. En DNA-profil er en liste over tal, baseret på de gentagne sekvenser, vi alle har.

Brugen af disse korte gentagelsessekvenser (det tekniske udtryk er "short tandem repeat" eller STR) startede i 1994, da UK Forensic Science Service identificerede fire af disse regioner. Chancen for, at to personer, der blev taget tilfældigt i befolkningen, ville dele de samme gentagelsestal i disse fire regioner, var omkring 1 ud af 50.000.

Nu er antallet af kendte gentagelsessekvenser udvidet kraftigt, hvor den seneste test ser på 24 STR-regioner. Brug af alle de kendte STR-regioner resulterer i en uendelig lille sandsynlighed for, at to tilfældige personer har den samme DNA-profil. And herein lies the power of DNA profiling.

How is DNA profiling performed?

The repeat sequence will be the same in every cell within a person—thus, the DNA profile from a blood sample will be the same as from a plucked hair, inside a tooth, saliva, or skin. It also means a DNA profile will not in itself indicate from what type of tissue it originated.

Consider a knife alleged to be integral to an investigation. A question might be "who held the knife"? A swab (cotton or nylon) will be moistened and rubbed over the handle to collect any cells present.

Swabbing an item left at a crime scene can easily yield enough cells to generate a DNA profile. Credit:Fuss Sergey/Shutterstock

The swab will then be placed in a tube containing a cocktail of chemicals that purifies the DNA from the rest of the cellular material—this is a highly automated process. The amount of DNA will then be quantified.

If there is sufficient DNA present, we can proceed to generate a DNA profile. The optimum amount of DNA needed to generate the profile is 500 picograms—this is really tiny and represents only 80 cells!

How foolproof is DNA profiling?

DNA profiling is highly sensitive, given it can work from only 80 cells. This is microscopic:the tiniest pinprick of blood holds thousands of blood cells.

Consider said knife—if it had been handled by two people, perhaps including a legitimate owner and a person of interest, yet only 80 cells are present, those 80 cells would not be from only one person but two. Hence there is now a less-than-optimal amount of DNA from either of the people, and the DNA profiling will be a mixture of the two.

Fortunately, there are several types of software to pull apart these mixed DNA profiles. However, the DNA profile might be incomplete (the term for this is "partial"); with less DNA data, there will be a reduced power to identify the person.

Worse still, there may be insufficient DNA to generate any meaningful DNA profile at all. If the sensitivity of the testing is pushed further, we might obtain a DNA profile from even a few cells. But this could implicate a person who may have held the knife innocently weeks prior to an alleged event; or be from someone who shook hands with another person who then held the knife.

This later event is called "indirect transfer" and is something to consider with such small amounts of DNA.

What can't DNA profiling do?

In forensics, using DNA means comparing a profile from a sample to a reference profile, such as taken from a witness, persons of interest, or criminal DNA databases.

By itself, a DNA profile is a set of numbers. The only thing we can figure out is whether the owner of the DNA has a Y-chromosome—that is, their biological sex is male.

A standard STR DNA profile does not indicate anything about the person's appearance, predisposition to any diseases, and very little about their ancestry.

Other types of DNA testing, such as ones used in genealogy, can be used to associate the DNA at a crime scene to potential genetic relatives of the person—but current standard STR DNA profiling will not link to anyone other that perhaps very close relatives—parents, offspring, or siblings.

DNA profiling has been, and will continue to be, an incredibly powerful forensic test to answer "whose biological material is this"? This is its tremendous strength. As to how and when that material got there, that's for different methods to sort out.

Sidste artikelKan vi helbrede frø-pandemien?

Næste artikelHvordan poliovirus overtager celler indefra

Varme artikler

Varme artikler

-

Hvorfor ser mitokondrier ud, som de gør?Kredit:Wikipedia commons En af de største udfordringer i biologien i dag er at forklare strukturen af cristae, mitokondriers indre membraner. En forklaring i dette tilfælde er et sæt principper t

Hvorfor ser mitokondrier ud, som de gør?Kredit:Wikipedia commons En af de største udfordringer i biologien i dag er at forklare strukturen af cristae, mitokondriers indre membraner. En forklaring i dette tilfælde er et sæt principper t -

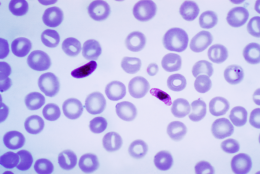

Forskere kortlægger narkotiske genomiske mål i udviklingen af malariaparasitDette mikrofotografi af en blodudstrygning indeholder en makro- og mikrogametocyt af parasitten Plasmodium falciparum. Kredit:Wikipedia. Forskere ved University of California San Diego School of M

Forskere kortlægger narkotiske genomiske mål i udviklingen af malariaparasitDette mikrofotografi af en blodudstrygning indeholder en makro- og mikrogametocyt af parasitten Plasmodium falciparum. Kredit:Wikipedia. Forskere ved University of California San Diego School of M -

Fem minutters gåture bedste måde at trøste grædende babyer på, siger undersøgelseEn mor leger med sin baby i deres hjem i Caracas, Venezuela. Videnskaben har perfektioneret svaret på at berolige en grædende baby:Hold og gå med dem i fem minutter. Den evidensbaserede beroligend

Fem minutters gåture bedste måde at trøste grædende babyer på, siger undersøgelseEn mor leger med sin baby i deres hjem i Caracas, Venezuela. Videnskaben har perfektioneret svaret på at berolige en grædende baby:Hold og gå med dem i fem minutter. Den evidensbaserede beroligend -

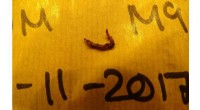

Regnorme kan formere sig i Mars jordsimulatorUng orm, født i mars jord simulant. Kredit:Wieger Wamelink, WUR To unge orme er de første afkom i et Mars jordforsøg på Wageningen University &Research. Biolog Wieger Wamelink fandt dem i en Mars

Regnorme kan formere sig i Mars jordsimulatorUng orm, født i mars jord simulant. Kredit:Wieger Wamelink, WUR To unge orme er de første afkom i et Mars jordforsøg på Wageningen University &Research. Biolog Wieger Wamelink fandt dem i en Mars

- NASA ser Tropical Depression 33W påvirke Filippinerne

- Hvornår lærte mennesker først at tælle?

- Team opnår første plasma på opgraderet MAST, klar til at teste Super-X divertor

- Sådan tolkes en beta-koefficient

- Metanbaserede brændstoffer til transport- og energisektoren

- FORKLARER:4 vil kredse om Jorden på 1. SpaceX privatflyvning